June 30, 2008

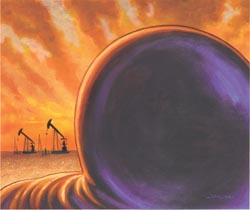

This economic panic is pushing the planet

right back down the agenda

Oil-dependent countries are focused on growth at all costs, and the pale green political consensus looks unlikely to hold

George Monbiot

The Guardian

July 1, 2008

Almost everyone seems to agree: governments now face a choice between saving the planet and saving the economy. As recession looms, the political pressure to abandon green policies intensifies. A report published yesterday by Ernst & Young suggests that the EU's puny carbon target will raise energy bills by 20% over the next 12 years. Last week the prime minister's advisers admitted to the Guardian that his renewable energy plans were "on the margins" of what people will tolerate.

But these fears are based on a false assumption: that there is a cheap alternative to a green economy. Last week New Scientist reported a survey of oil industry experts, which found that most of them believe global oil supplies will peak by 2010. If they are right, the game is up. A report published by the US department of energy in 2005 argued that unless the world begins a crash programme of replacements 10 or 20 years before oil peaks, a crisis "unlike any yet faced by modern industrial society" is unavoidable.

If the world is sliding into recession, it's partly because governments believed that they could choose between economy and ecology. The price of oil is so high and it hurts so much because there has been no serious effort to reduce our dependency. Yesterday in the Guardian, Rajendra Pachauri suggested that an impending recession could force us to confront the flaws in the global economy. Sadly it seems so far to have had the opposite effect: a recent Ipsos Mori poll suggests that people are losing interest in climate change. Opportunities for energy populism abound: it cannot be long before one of the major parties abandons the pale green consensus and starts invoking an oil cornucopia it cannot possibly deliver.

The British government maintains both positions at once. In his speech last week, Gordon Brown said he wanted "to facilitate a reduction in short-term global oil prices" while seeking "to reduce progressively our dependence on oil". He knows that the first objective makes the second one harder to achieve. The government's policy is to build more of everything - more coal plants, more nuclear power, more oil rigs, more renewables, more roads, more airports - and hope no one spots the contradictions.

Is there a way out? Could we abandon the fossil fuel economy without provoking a blistering backlash? Two things are obvious. We need a global system, and the current one, the Kyoto protocol, is bust. It sets no cap on global carbon pollution, its targets bear no relation to current science and are unenforceable anyway, it contains loopholes and get-out clauses wide enough to sail an oil tanker through.

Until recently I supported an alternative system called contraction and convergence. Every country, this system proposes, should end up with the same quota of carbon dioxide per person. The richest countries must produce much less than they do today; the poorest ones could pollute more. Another proposal flows logically from this one: carbon rationing. Having been assigned its carbon quota, each nation would divide up part of it equally among its citizens, who could use it to buy energy or trade it among themselves. These proposals have the merit of capping global pollution, of being fair, progressive and easy to understand and of encouraging us to think about our use of energy.

But, after reading the proofs of a book by the independent thinker Oliver Tickell, to be published next month, I have changed my view. In Kyoto2: How to Manage the Global Greenhouse, Tickell slaughters my favourite ideas. He shows that there is no logical basis for dividing up the right to pollute among nation states. It gives them too much power over this commodity, and there is no guarantee that they would pass the pollution rights on to their citizens, or use the money they raised to green the economy. Carbon rationing, he argues, requires a level of economic literacy that's far from universal in the most advanced economies, let alone in countries where most people don't have bank accounts.

Instead Tickell proposes setting a global limit for carbon pollution then selling permits to pollute to companies extracting or refining fossil fuels. This has the advantage of regulating a few thousand corporations - running oil refineries, coal washeries, gas pipelines and cement and fertiliser works for example - rather than a few billion citizens. These firms would buy their permits in a global auction, run by a coalition of the world's central banks. There's a reserve price, to ensure that the cost of carbon doesn't fall too low, and a ceiling price, at which the banks promise to sell permits, to ensure that the cost doesn't cripple the global economy. In this case companies would be borrowing permits from the future. But because the money raised would be invested in renewables, the demand for fossil fuels would fall, so fewer permits would need to be issued in later years.

Tickell calculates that if the cap were set low enough to ensure that the world became carbon neutral by 2050, the total cost of permits would be about $1 trillion a year, or roughly 1.5% of the global economy. The money would be spent on helping the poor to adapt to climate change, paying countries to protect forests and other ecosystems, developing low-carbon farming, promoting energy efficiency and building renewable power plants.

But his figure seems too low. Like many of the world's climate scientists, Oliver Tickell proposes that the concentration of greenhouse gases should eventually be stabilised at 350 parts per million (carbon dioxide equivalent) in the atmosphere, and his calculations are based on this target. Last week Lord Stern suggested that meeting a less stringent target (500 parts per million) would cost 2% of world gross domestic product. If the price of the carbon permits sold at auction were much higher than Tickell suggests, the extra money could be used for massive tax rebates and social spending, aimed especially at the poor. But could the world afford it?

This money doesn't disappear, it gets spent. Tickell's proposal could represent a classic Keynesian solution to economic crisis. The $1, $2 or even $5 trillion the system would cost is used to kick-start a green industrial revolution, a new New Deal not that different from the original one (whose most successful component was Roosevelt's Civilian Conservation Corps, which protected forests and farmland). This would not be the first time that business was rescued by the measures it most stoutly resists: there's a long history of corporate lobbying against the kind of government spending that eventually saves the corporate economy.

Do we want to save it, even if we can? It is hard to see how the current global growth rate of 3.7% a year (which means the global economy doubles every 19 years) could be sustained, even if the whole thing were powered by the wind and the sun. But that is a question for another column and perhaps another time, when the current economic panic has abated. For now we have to find a means of saving us from ourselves.

monbiot.com

More pipeline capacity needed

New lines worth $23B may be on way

Reuters, Calgary Herald

Friday, June 27, 2008

Capacity is tight on Canada's crude oil pipelines, but as much as $23 billion in new lines could be on the way to help supply current and as-yet-untapped markets, the country's energy regulator said Thursday.

The National Energy Board said new pipeline space is needed to handle rising production from the oilsands and to give producers flexibility in where they can ship their crude.

In a report on the 45,000 kilometres of oil and gas pipelines it regulates, the NEB said there was some rationing of space in 2007 on Enbridge Inc.'s 1.9 million barrel a day system to the U.S. Midwest and beyond, and that the system ran at or near capacity in this year's first quarter.

The industry will get some relief in November when Kinder Morgan Energy Partners is slated to have a 40,000 barrel a day expansion of its Trans Mountain system to the West Coast completed, the board said.

The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers estimated last week that the country's production could nearly double to 4.5 million barrels a day by 2020, as a host of new oil sands projects start up.

That has the oil industry considering new markets, such as the U.S. Gulf Coast, California and Asia.

Pipeline projects currently under development include Enbridge's 450,000 barrel a day Alberta Clipper project to Superior, Wisc., from Hardisty, Alta., and TransCanada Corp.'s 590,000 barrel a day Keystone line to Southern Illinois and Oklahoma from Alberta.

Keystone is scheduled to be in service late next year and Alberta Clipper in 2010.

Among longer-term proposals, TransCanada is considering a 750,000 barrel a day pipeline to Texas as well as a 400,000 barrel a day line to California.

Enbridge has rekindled plans for the 400,000 barrel a day Gateway line, which would ship Alberta crude to the West Coast, where it could be loaded on tankers bound for Asia.

It is also studying the re-reversal of Line nine between Sarnia, Ont., and Montreal to give Quebec refiners access to western Canadian crude.

Use of natural gas pipelines, meanwhile, declined with waning western Canadian gas production and increased competition with western U.S. supply basins in 2007, the NEB said.

"Pipeline capacity is adequate across the country although there may be occasions of short-term limitation at some points depending upon markets, storage and seasonal shifts," it said.

© The Calgary Herald 2008

Suppose Alberta had this huge surplus - wait, it does!

JEFFREY SIMPSON

Globe and Mail

June 27, 2008

Later this summer, the Alberta government will announce the first-quarter estimate for its 2008-2009 budget surplus.

On budget day, the government based its analysis on $78-a-barrel oil. It predicted a $1.6-billion surplus, even after huge spending increases.

With oil trading between $130 and $140 a barrel, it now looks as if the Alberta budget surplus for this fiscal year will be between $11-billion and $12-billion. Forecasters are already suggesting that the 2009-2010 budget surplus could hit $20-billion.

In Ottawa, the Harper government bought Quebec's argument that a "fiscal imbalance" existed between the federal government and the provinces. The argument ran that Ottawa had too much money, and provinces too little. So Ottawa had to hand over billions of dollars, which the Harper government did.

That was a so-called vertical imbalance between two levels of government. Canada now faces the most severe horizontal imbalance since the 1970s. One province, Alberta, has a surplus 10 times greater than Ottawa's and larger than all the provincial surpluses combined. In fact, Alberta's surplus will be greater than the federal and other provincial surpluses combined.

If oil prices remain high, or go higher, the huge gap between Alberta's revenues (and, to a lesser extent, Saskatchewan's) will widen every year.

Until now, almost no one in the country dared mention this gap. People outside of Alberta were scared of conjuring up memories of the Trudeau era's national energy program. People thought oil would settle back to a lower price. The Alberta government was soaking up the surpluses with a spending spree on infrastructure and health care. The gaps were big, but not that big.

What, if anything, will the national government do faced with this horizontal imbalance? Chances are, nothing, given the Harper government's political base in Alberta and its belief in "open federalism," which invariably translates into letting provinces pretty much do what they want and allowing the chips to fall where they will.

Very high oil prices, however, bring a series of jarring adjustments that do affect Ottawa's ability to run the economy.

The equalization formula, for example, is going to be so out of whack that the Toronto-Dominion Bank anticipates Ontario will be receiving payments from Ottawa within two years.

The Bank of Canada has refused to lower interest rates because it's worried about inflation produced by higher energy (and food) costs.

Manufacturers won't like this approach, since they're being terribly squeezed, but the soaring costs of energy make the bank fear inflation.

The high dollar stems, in part, from the incredible infusion of money into the country from high oil prices that produce gains for producers and losses for consumers. Good luck telling a manufacturer that a dollar at parity with the greenback is a good thing when a productivity gap exists between the United States and Canada.

The Alberta boom sucks up labour from less fortunate parts of Canada. Labour markets, in this sense, are working. Some of the money earned in that province works its way to other parts of Canada, but the gap in the ability of citizens to receive public services among provinces widens.

A national government twice tried to grapple with such huge regional spreads caused by high oil prices. Everyone remembers the NEP, but it's often forgotten that Joe Clark's government tried in 1979 to negotiate a deal with then-premier Peter Lougheed to recycle some of Alberta's petro-revenues across the country. The negotiations were extremely difficult. They remained unfinished when the Clark government fell, with consequences for Alberta.

There will be fierce resistance in Alberta to even discussing the huge challenges associated with this burgeoning gap. We give through equalization, many Albertans will say. End of story. People such as Mr. Lougheed worry about the problem; the current government in Edmonton does not.

A few Albertans talk privately about how the province can spread at least some of its money across the country. Alberta, for example, could take $2-billion of that surplus and launch a crash program with industry and universities across Canada to solve the technical problems of sequestering carbon emissions.

The Harperites apparently won't say boo about the gap, even though the gap makes their life harder as a national government. Since no one can get near Mr. Harper to ask him a question, his views on the situation are unknown.

June 29, 2008

Oil disquiet on the Western front

North American media, Andrew Nikiforuk says, take for granted how much oil undermines democracy, powers our food system, feeds our drug-addled medical industry and concentrates our cities like bovine feedlots

ANDREW NIKIFORUK

Globe and Mail

June 28, 2008

Oil has fantastic powers: Like the genie from One Thousand and One Nights, it can grant impossible political wishes both fair and foul. This is why the U.S. oil baron John D. Rockefeller once, in a moment of reflection, called oil "the Devil's tears," and why Sheik Ahmed Zaki Yamani, in a moment of exasperation, wished that Saudi Arabia had discovered water, and why the late Venezuelan writer Jose Ignacio Cabrujas, in a moment of subversion, wrote that oil can create "a culture of miracles" that erases memory.

Canadians, the newly minted inhabitants of "an emerging energy superpower," now stand at the gas pumps cursing the price of oil and the prospect of shortened summer vacations. Yet they forget that many of our ancestors agonized about the price of slaves only 200 years ago. We too complained bitterly about the cost of feeding indentured labour, and dismissed the ugly rhetoric of abolitionists as offensive.

A barrel of oil, as analyst Dave Hughes often reminds me, equals 8.6 years of human labour. Think about that. "A human life span could produce about three barrels of oil-equivalent energy," he adds. We often miss this Hummer-sized truth because, as the Arabs know, petroleum induces lazy thinking and even lazier economics.

In fact, the North American media take for granted how much oil undermines democracy, powers our food system, feeds our drug-addled medical industry and concentrates our cities like bovine feedlots. It has done so as assuredly as cheap labour built Rome. "Slavery," a Wall Street Journal scribe recently wrote, "was the oil business of its time - profitable, essential, permitting piracy, demanding collusion in countless ills."

I don't think anyone has yet written a good book about how oil has replaced the true meaning of capital, let alone the energy of slaves, but Walter Youngquist has certainly chronicled the miraculous importance of "the Petroleum Interval." Youngquist, the author of GeoDestinies: The Inevitable Control of Earth Resources Over Nations and Individuals (National Book Company, 1997), is no green prophet. For most of his life, the thoughtful, Oregon-based geologist has worked for the world's major oil companies in 70 countries.

Unlike most environmentalists, Youngquist sensibly appreciates the versatility and portability of oil. But unlike most economists, he recognizes that oil is a finite treasure and that most of the world's endowment (the so-called cheap stuff) has been consumed in less than one human lifetime. The oil glass, now half empty, sits on a global table where China and India want a long draught of the economic elixir too. "There is no parallel in history for such a rapid development of and use of a resource as in the case of oil. ... It will be but a brief bright blip on the screen of human history."

Although Youngquist's book is now dated, his wisdom is not. Just a decade ago, he predicted that converting food to gasoline was wasteful nonsense; that industry's faith-based ideology in "technological fixes" was no answer to unrestrained growth; and that the tar sands could not prolong the Petroleum Interval. However, he did think the sands' prudent, well-sequenced development would be "important to Canada as a long-term source of energy and income." He recommended that we conserve the resource, not liquidate it.

Although debates about tar sands and its dirty character now dominate the news, most Canadians still know little about the world's largest energy project. But Larry Pratt does and did. In 1976, then a University of Alberta political scientist, he recognized that this Earth-destroying economy (and that's just what it is) would change the nation. His brilliant book The Tar Sands: Syncrude and the Politics of Oil (Hurtig, 1976) makes for disturbingly prescient reading today.

Pratt argued that the rapid development of the tar sands, which seemed imminent in the 1970s, would hollow out the nation's economy, enrich multinationals, impoverish Alberta and create what even federal bureaucrats then called "a biologically barren wasteland" along the Athabasca River. Pratt also recognized that the tar sands concerned us all: "Every Canadian, and every Canadian's children and their children, have a stake in the future of development of our energy resources." From an environmental standpoint, he predicted that Alberta was "walking blindfolded into the industrialization of the tar sands."

Even an industry consultant told Pratt, more than 30 years ago, "that before commencing development on the scale presently being contemplated, the government should have initiated ecological studies back about 1948 to monitor water flows, climate changes, soil conditions, temperature inversions etc., on a long-term basis. But such concerns were not taken seriously."

In the past decade, the moral carelessness of the Alberta and federal governments has grown exponentially. As a consequence, even U.S. mayors and British energy consumers are now talking about Canada's "dirty oil," because bitumen, no matter how you spin it, is a corrosive, smog-making, water-fouling, bottom-of-the-barrel product. Make no mistake about it: Canada now faces an intractable political emergency. It can either slow down tar sands development to serve a planned national transition to renewable energy sources, or it can rape the world's last great oil field and put the nation on a road to hell.

But however destructive the energy policies of government may be, the root of the problem "is always to be found in private life." That is the argument of U.S. man of letters and farmer Wendell Berry in Sex, Economy, Freedom and Community (Pantheon, 1993), and I share it reluctantly because of its inconvenient and personal implications: The boreal forest and the Mackenzie River basin aren't being destroyed by bad oilmen, but by popular demand and my driving habits. Berry's book, as fresh as newly baked bread, stands as one of the most powerful and conservative critiques of North American life ever written. "We face a choice that is starkly simple: we must change or be changed. If we fail to change for the better, then we will be changed for the worse."

Canadians, a mining people, now face a challenge more daunting than Ypres at the pumps and in the sands.

Andrew Nikiforuk's next book, The Tar Sands: Dirty Oil and the Future of a Continent, will be published this fall.

Envisioning a world of $200-a-barrel oil

As forecasters take that possibility more seriously, they describe fundamental shifts in the way we work, where we live and how we spend our free time.

By Martin Zimmerman

Los Angeles Times

June 28, 2008

The more expensive oil gets, the more Katherine Carver's life shrinks. She's given up RV trips. She stays home most weekends. She's scrapped her twice-a-month volunteer stint at a Malibu wildlife refuge -- the trek from her home in Palmdale just got too expensive.

How much higher would fuel prices have to go before she quit her job? Already, the 170-mile round-trip commute to her job with Los Angeles County Child Support Services in Commerce is costing her close to $1,000 a month -- a fifth of her salary. It's got the 55-year-old thinking about retirement.

"It's definitely pushing me to that point," Carver said.

The point could be closer than anyone thinks.

Three months ago, when oil was around $108 a barrel, a few Wall Street analysts began predicting that it could rise to $200. Many observers scoffed at the forecasts as sensational, or motivated by a desire among energy companies and investors to drive prices higher.

But with oil closing above $140 a barrel Friday, more experts are taking those predictions seriously -- and shuddering at the inflation-fueled chaos that $200-a-barrel crude could bring. They foresee fundamental shifts in the way we work, where we live and how we spend our free time.

"You'd have massive changes going on throughout the economy," said Robert Wescott, president of Keybridge Research, a Washington economic analysis firm. "Some activities are just plain going to be shut down."

Besides the obvious effect $7-a-gallon gasoline would have on commuters, automakers, airlines, truckers and shipping firms, $200 oil would drive up the price of a broad spectrum of products: Insecticides and hand lotions, cosmetics and food preservatives, shaving cream and rubber cement, plastic bottles and crayons -- all have ingredients derived from oil.

The pain would probably be particularly intense in Southern California, which is known for its long commutes and high cost of living.

"Throughout our history, we have grown on the assumption that energy costs would be low," said Michael Woo, a former Los Angeles city councilman and a current member of the city Planning Commission. "Now that those assumptions are shifting, it changes assumptions about housing, cars and how cities grow."

Push prices up fast enough, he said, and "it would be the urban-planning equivalent of an earthquake."

Consumers

With every penny hike in the price of gas costing American consumers about $1 billion a year, sharply higher pump prices would lead to "significant bankruptcies and store closings," said Scott Hoyt, director of consumer economics at Moody's Economy.com.

Consumer spending has held up surprisingly well in the face of skyrocketing pump prices -- bolstered in part, perhaps, by federal tax rebates. But the same day the government reported a 0.8% rise in May consumer spending, a research firm said consumer confidence had plunged to its lowest level since 1980 -- hinting at the catastrophic effect another big gas price surge could have on retailers and customers.

"The purchasing power of the American people would be kicked in the teeth so darned hard by $200-a-barrel oil that they won't have the ability to buy much of anything," said S. David Freeman, president of the L.A. Board of Harbor Commissioners and author of the 2007 book "Winning Our Energy Independence."

BIGresearch of Worthington, Ohio, said more than half of Californians in a recent survey said they were driving less because of high gas prices. Almost 42% said they had reduced vacation travel and 40% said they were dining out less.

If any retailers would benefit, it would be those on the Internet. In a recent survey by Harris Interactive, one-third of adults said high gas prices had made them more likely to shop online to avoid driving.

Restaurant operators such as Brinker International, which owns the Chili's and Romano's Macaroni Grill chains, are suffering and are likely to struggle even more as consumers look for ways to reduce spending. Fast-food chains wouldn't be immune, experts say, although they might fare better as families downscale their dining choices.

Vehicle sales, too, would probably continue to tank. Sales of new cars, sport utility vehicles and light trucks fell more than 18% in California in the first quarter compared with a year earlier. Although some consumers have been shopping for smaller, more fuel-efficient vehicles, many dealers are demanding premiums for gas-sipping hybrids, wiping out much of the financial advantage of buying one.

Nationwide, $200 oil and $7 gasoline would force Americans to take 10 million vehicles off the roads over the next four years, Jeff Rubin, chief economist at CIBC World Markets, wrote in a recent report.

As for the state's beleaguered housing market, prices are falling faster in areas requiring long commutes -- such as Lancaster and Palmdale -- than in neighborhoods closer to job centers.

Sky-high gas prices "would basically reorient society to where proximity would be more valuable," said Tom Gilligan, finance professor at USC.

Americans may also feel the effects of a rise in energy-related crime. Ads for locking gas caps are becoming more prevalent. Restaurant owners are complaining that thieves are helping themselves to used barrels of cooking oil, which can be home-brewed into biodiesel fuel.

Transportation

Workers stuck with long commutes and gas-guzzling cars would look increasingly to public transit, experts say.

Already Californians' mobility is being curbed. Traffic on the state's freeways fell almost 4% in April compared with a year earlier, and ridership on many subway and bus lines operated by the L.A. County Metropolitan Transportation Authority has risen in recent months.

But a huge influx of riders would strain aspects of the system, MTA says, noting that many buses are overcrowded at rush hour now.

Quickly adding capacity to meet demand from new riders wouldn't be easy, because new buses cost hundreds of thousands of dollars and take up to two years to deliver.

Transit advocate Kymberleigh Richards said new riders on popular routes such as Wilshire Boulevard, Vermont Avenue or Sherman Way in the San Fernando Valley "are going to have a bit of a culture shock. It's a different world to be using public transit when you're used to being in your own vehicle by yourself."

Just how many drivers would become public-transit riders if oil surges to $200 a barrel is hard to predict, but there's a big pool of potential customers. About 87% of Southern Californians commute by car, according to 2005 data from transportation expert Alan Pisarski. That compares with 63% in New York and its environs.

Travelers can also expect much fuller airplanes and much more expensive flights -- when they're available at all. Delta Air Lines Inc., for example, recently said it was cutting about 13% of its flights from Los Angeles International Airport to save fuel.

It also could mean shifting flights from outlying airports such as Ontario to LAX to cut overhead costs, said Jack Kyser, chief economist for the Los Angeles County Economic Development Corp. Carriers probably would also trim flights in highly competitive air corridors such as L.A. to the San Francisco Bay Area.

Even the cost of getting away from it all on Santa Catalina Island would go up. Greg Bombard, president of the Catalina Express ferry service, has trimmed schedules, raised fares and reduced hiring to make up for fuel costs that have risen sevenfold since 2002. Another big increase and he says he'll have to ask state regulators, who control his rates, to OK another fare hike.

Trade

The fee increases on the ferry would be nothing compared with the added cost of transoceanic shipping if oil goes to $200. Some experts say high energy costs are altering global trade and slowing the pace of globalization.

It takes about 7,000 tons of bunker-fuel to fill the tanks of a 5,000-container cargo ship for a trip from Shanghai to Los Angeles. Over the last year and half, the cost of that fuel has jumped 87% to $552 a ton, according to the World Shipping Council, boosting the cost of a fill-up to more than $3.8 million.

"To put things in perspective, today's extra shipping cost from East Asia is the equivalent of imposing a 9% tariff on East Asian goods entering North America," said Rubin of CIBC World Markets. "At $200 per barrel, the tariff equivalent rate will rise to 15%."

If oil continues to rise from current levels, officials at the Port of Los Angeles believe West Coast ports would gain business because they are 10 to 12 days' sailing time from Asia, versus the 18-to-20-day route from Asia to the East Coast through the Panama Canal.

But local ports could lose business if shipping costs get so out of hand that companies begin shifting production back to North America from Asia -- something that's happening in the steel industry, Rubin said.

Local distribution patterns could change too. Stephen Gaddis, chief executive of Pacific Cheese Co., a Hayward, Calif., cheese processing and packaging firm, thinks high fuel prices will push restaurants, retailers and food manufacturers to look for suppliers closer to their operations.

"Local sourcing is ideal. You won't pay as much for freight, and when you use less fuel it's better for the environment," Gaddis said.

Soaring diesel prices will make companies rethink whether they should have large, centralized plants or build smaller ones around the country.

That's what Pacific Cheese is doing. It's building a packaging plant in Texas to be closer to one of its larger suppliers and expects to serve its Southwestern clients from there.

In the near future, however, consumers can expect to pay for the higher cost of producing food and moving it around the country, say food executives, farmers and economists. Even having a deep-dish pizza with extra cheese brought to your door costs more now that chains such as Pizza Hut are charging for delivery.

The workplace

Dramatically higher transportation costs would usher in an era of virtual mobility, or zero mobility, for many workers.

"We're seeing companies go to four-day workweeks, place increased emphasis on working at home, show bigger interest in setting up satellite offices -- anything that gets commute times down and gets people off the road," said analyst Rob Enderle of Enderle Group in San Jose.

Videoconferencing, touted as "the next big thing" for years, would finally have its day, thanks to improved technology and a desperation to cut corporate travel budgets.

Telecommuting, or working from home, is easier than ever because of the spread of high-speed Internet access, said Jonathan Spira, chief analyst at Basex Inc., a business research firm in New York. In particular, workers in "knowledge" jobs that can be performed with computers and phones would benefit.

But Gilligan of USC noted that lower-income workers tend to be in jobs that don't favor telecommuting, such as retail and food service.

"These are the same people who are already being creamed by the mortgage crisis," he said. "The impacts of energy price increases are highly disparate."

Although white-collar workers may be able to telecommute, they could also take a serious financial hit because soaring energy prices tend to wreak havoc on the stock market. The explosion of 401(k) plans and similar retirement accounts in the last few decades -- and the decline of traditional pensions with guaranteed payouts -- have tied workers' financial futures more closely to stocks than they were during the 1970s oil shocks. A prolonged Wall Street downturn could mean a no-frills retirement, or none at all.

Upsides

It wouldn't all be bad, of course. Some industries could boom, providing jobs and tax dollars. California has seen a jump in drilling activity as oil companies try to extract more crude from the state's fields. Regulators expect a record 4,000 wells to be drilled in the state this year.

"Every rig and every crew that's available is working right now," said Hal Bopp, the state's oil and gas supervisor.

And as rising oil prices make alternative-fuel vehicles more cost-effective, California companies such as Tesla Motors Inc., which recently began production of a $100,000 all-electric sports car, could become important leaders in an emerging industry.

Tourist attractions may also see an upswing in local business as families look for less-expensive vacation alternatives close to home. A recent survey by travel insurer Access America found that 26% of Americans would cut back on recreational travel as a first response to higher gas prices.

In Southern California, with its many natural wonders, theme parks and other attractions, the prospect of a "staycation" may be less disappointing than for a resident of, say, Nebraska. And movies, a staple of the local economy, may prosper as Americans seek escapism and a (relatively) cheap night out.

And spending less time stuck in traffic on the 405? Priceless.

"More carpooling, fewer people on the freeways, more telecommuting -- in many ways, what would happen is what people have been trying to make happen for a long time," USC's Gilligan said.

Times staff writers Ken Bensinger, Leslie Earnest, Jerry Hirsch, Peter Pae and Ronald D. White contributed to this report.

June 24, 2008

Global Warming Twenty Years Later

see also Put oil firm chiefs on trial

by James Hansen

www.worldwatch.org

June 23, 2008

Tipping Points Near

Today, I will testify to Congress about global warming, 20 years after my June 23, 1988 testimony, which alerted the public that global warming was under way. There are striking similarities between then and now, but one big difference.

Again a wide gap has developed between what is understood about global warming by the relevant scientific community and what is known by policymakers and the public. Now, as then, frank assessment of scientific data yields conclusions that are shocking to the body politic. Now, as then, I can assert that these conclusions have a certainty exceeding 99 percent.

The difference is that now we have used up all slack in the schedule for actions needed to defuse the global warming time bomb. The next President and Congress must define a course next year in which the United States exerts leadership commensurate with our responsibility for the present dangerous situation.

Otherwise, it will become impractical to constrain atmospheric carbon dioxide, the greenhouse gas produced in burning fossil fuels, to a level that prevents the climate system from passing tipping points that lead to disastrous climate changes that spiral dynamically out of humanity's control.

Changes needed to preserve creation, the planet on which civilization developed, are clear. But the changes have been blocked by special interests, focused on short-term profits, who hold sway in Washington and other capitals.

I argue that a path yielding energy independence and a healthier environment is, barely, still possible. It requires a transformative change of direction in Washington in the next year.

Then: Time to "Stop Waffling"

On June 23, 1988, I testified to a hearing chaired by Senator Tim Wirth of Colorado that the Earth had entered a long-term warming trend, and that human-made greenhouse gases almost surely were responsible. I noted that global warming enhanced both extremes of the water cycle, meaning stronger droughts and forest fires, on the one hand, but also heavier rains and floods.

My testimony two decades ago was greeted with skepticism. But while skepticism is the lifeblood of science, it can confuse the public. As scientists examine a topic from all perspectives, it may appear that nothing is known with confidence. But from such broad open-minded study of all data, valid conclusions can be drawn.

My conclusions in 1988 were built on a wide range of inputs from basic physics, planetary studies, observations of ongoing changes, and climate models. The evidence was strong enough that I could say it was time to "stop waffling." I was sure that time would bring the scientific community to a similar consensus, as it has.

While international recognition of global warming was swift, actions have faltered. The United States refused to place limits on its emissions, and developing countries such as China and India rapidly increased their emissions.

The Coming Storm

What is at stake? Warming so far, about two degrees Fahrenheit over land areas, seems almost innocuous, being less than day-to-day weather fluctuations. But more warming is already "in-the-pipeline," delayed only by the great inertia of the world ocean. And climate is nearing dangerous tipping points. Elements of a "perfect storm," a global cataclysm, are assembled.

Climate can reach points such that amplifying feedbacks spur large rapid changes. Arctic sea ice is a current example. Global warming initiated sea ice melt, exposing darker ocean that absorbs more sunlight, melting more ice. As a result, without any additional greenhouse gases, the Arctic soon will be ice-free in the summer.

More ominous tipping points loom. West Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets are vulnerable to even small additional warming. These two-mile-thick behemoths respond slowly at first, but if disintegration gets well under way it will become unstoppable. Debate among scientists is only about how much sea level would rise by a given date. In my opinion, if emissions follow a business-as-usual scenario, sea level rise of at least two meters is likely this century. Hundreds of millions of people would become refugees. No stable shoreline would be reestablished in any time frame that humanity can conceive.

Animal and plant species are already stressed by climate change. Polar and alpine species will be pushed off the planet, if warming continues. Other species attempt to migrate, but as some are extinguished, their interdependencies can cause ecosystem collapse. Mass extinctions, of more than half the species on the planet, have occurred several times when the Earth warmed as much as expected if greenhouse gases continue to increase. Biodiversity recovered, but it required hundreds of thousands of years.

Getting to 350 ppm

The disturbing conclusion, documented in a paper[1] I have written with several of the world's leading climate experts, is that the safe level of atmospheric carbon dioxide is no more than 350 ppm (parts per million), and it may be less. Carbon dioxide amount is already 385 ppm and rising by about 2 ppm per year. Stunning corollary: the oft-stated goal to keep global warming less than two degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) is a recipe for global disaster, not salvation.

These conclusions are based on paleoclimate data showing how the Earth responded to past levels of greenhouse gases and on observations showing how the world is responding to today's carbon dioxide amount. The consequences of continued increase of greenhouse gases extend far beyond extermination of species and future sea level rise.

Arid subtropical climate zones are expanding poleward. Already an average expansion of about 250 miles has occurred, affecting the southern United States, the Mediterranean region, Australia, and southern Africa. Forest fires and drying-up of lakes will increase further unless carbon dioxide growth is halted and reversed.

Mountain glaciers are the source of fresh water for hundreds of millions of people. These glaciers are receding worldwide, in the Himalayas, Andes, and Rocky Mountains. They will disappear, leaving their rivers as trickles in late summer and fall, unless the growth of carbon dioxide is reversed.

Coral reefs, the rainforests of the ocean, are home for one-third of the species in the sea. Coral reefs are under stress for several reasons, including warming of the ocean, but especially because of ocean acidification, a direct effect of added carbon dioxide. Ocean life dependent on carbonate shells and skeletons is threatened by dissolution as the ocean becomes more acid.

Such phenomena, including the instability of Arctic sea ice and the great ice sheets at today's carbon dioxide amount, show that we have already gone too far. We must draw down atmospheric carbon dioxide to preserve the planet we know. A level of no more than 350 ppm is still feasible, with the help of reforestation and improved agricultural practices, but just barely - time is running out.

Moving Away from Fossil Fuels

Requirements to halt carbon dioxide growth follow from the size of fossil carbon reservoirs. Coal towers over oil and gas. Phasing out the use of coal except where the carbon is captured and stored below ground is the primary requirement for solving global warming.

Oil is used in vehicles, where it is impractical to capture the carbon. But oil is running out. To preserve our planet we must ensure that the next mobile energy source is not obtained by squeezing oil from coal, tar shale, or other fossil fuels.

Fossil fuel reservoirs are finite, which is the main reason that prices are rising. We must move beyond fossil fuels eventually. Solution of the climate problem requires that we move to carbon-free energy promptly.

Special interests have blocked the transition to our renewable energy future. Instead of moving heavily into renewable energies, fossil fuel companies choose to spread doubt about global warming, just as tobacco companies discredited the link between smoking and cancer. Methods are sophisticated, including funding to help shape school textbook discussions of global warming.

CEOs of fossil energy companies know what they are doing and are aware of the long-term consequences of continued business as usual. In my opinion, these CEOs should be tried for high crimes against humanity and nature.

But the conviction of ExxonMobil and Peabody Coal CEOs will be no consolation if we pass on a runaway climate to our children. Humanity would be impoverished by ravages of continually shifting shorelines and intensification of regional climate extremes. Loss of countless species would leave a more desolate planet.

If politicians remain at loggerheads, citizens must lead. We must demand a moratorium on new coal-fired power plants. We must block fossil fuel interests who aim to squeeze every last drop of oil from public lands, off-shore, and wilderness areas. Those last drops are no solution. They yield continued exorbitant profits for a short-sighted, self-serving industry, but no alleviation of our addiction or long-term energy source.

Pricing Carbon Emissions

Moving from fossil fuels to clean energy is challenging, yet it is also transformative in ways that will be welcomed. Cheap, subsidized fossil fuels engendered bad habits. We import food from halfway around the world, for example, even with healthier products available from nearby fields. Local produce would be competitive were it not for fossil fuel subsidies and the fact that climate change damages and costs, due to fossil fuels, are also borne by the public.

A price on emissions that cause harm is essential. Yes, a carbon tax. A carbon tax with a 100 percent dividend[2] is needed to wean us off of our fossil fuel addiction. A tax and dividend allows the marketplace, not politicians, to make investment decisions.

A carbon tax on coal, oil, and gas is simple, applied at the first point of sale or port of entry. The entire tax must be returned to the public-an equal amount to each adult, a half-share for children. This dividend can be deposited monthly in an individual's bank account.

A carbon tax with a 100 percent dividend is non-regressive. On the contrary, you can bet that low- and middle-income people will find ways to limit their carbon tax and come out ahead. Profligate energy users will have to pay for their excesses.

Demand for low-carbon, high-efficiency products will spur innovation, making U.S. products more competitive on international markets. Carbon emissions will plummet as energy efficiency and renewable energies grow rapidly. Black soot, mercury, and other fossil fuel emissions will decline. A brighter, cleaner future, with energy independence, is possible.

America's Role

Washington likes to spend our tax money line-by-line. Swarms of high-priced lobbyists in alligator shoes help Congress decide where to spend, and in turn the lobbyists' clients provide "campaign" money.

The public must send a message to Washington. Preserve our planet, and creation, for our children and grandchildren, but do not use that as an excuse for more tax-and-spend. Let this be our motto: "One hundred percent dividend or fight!"

The next President must make a national low-loss electric grid an imperative. It will allow dispersed renewable energies to supplant fossil fuels for power generation. Technology exists for direct-current high-voltage buried transmission lines. Trunk lines can be completed in less than a decade and expanded, in a way analogous to interstate highways.

Government must also change utility regulations so that profits do not depend on selling ever more energy, but instead increase with efficiency. Building-code and vehicle-efficiency requirements must be improved and put on a path toward carbon neutrality.

The fossil fuel industry maintains its stranglehold on Washington via demagoguery, using China and other developing nations as scapegoats to rationalize inaction. In fact, the United States produced most of the excess carbon in the air today, and it is to our advantage as a nation to move smartly in finding ways to reduce emissions. As with the ozone problem, developing countries can be allowed limited extra time to reduce emissions. They will cooperate: they have much to lose from climate change and much to gain from clean air and reduced dependence on fossil fuels.

The United States must establish fair agreements with other countries. However, our own tax and dividend should start immediately. We have much to gain from it as a nation, and other countries will copy our success. If necessary, import duties on products from uncooperative countries can level the playing field, with the import tax added to the dividend pool.

Democracy works, but sometimes it churns slowly. Time is short. The 2008 election is critical for the planet. If Americans turn out to pasture the most brontosaurian congressmen, and if Washington adapts to address climate change, our children and grandchildren can still hold great expectations.

Dr. James E. Hansen, a physicist by training, directs the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, a laboratory of the Goddard Space Flight Center and a unit of the Columbia University Earth Institute, but he testifies here as a private citizen.

[1] J. Hansen et al., "Target Atmospheric CO2: Where Should Humanity Aim?" submitted 18 June 2008. See http://arxiv.org/abs/0804.1126 and http://arxiv.org/abs/0804.1135.

[2] The proposed "tax and 100% dividend" is based largely on the cap-and-dividend approach described by Peter Barnes in Who Owns the Sky: Our Common Assets and the Future of Capitalism (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2001). See http://www.ppionline.org/ppi_ci.cfm?knlgAreaID=116&subsecID=149&contentID=3867.

June 23, 2008

Put oil firm chiefs on trial,

says leading climate change scientist

Turning Up the Heat on Climate Issue

David A. Fahrenthold, Washington Post, 23-Jun-2008

Put oil firm chiefs on trial, says leading climate change scientist

Ed Pilkington, The Guardian, 23-Jun-2008

see also Global warming twenty years later

Turning Up the Heat on Climate Issue

20 Years Ago, a 98-Degree Day Illustrated Scientist's Warning

By David A. Fahrenthold

Washington Post Staff Writer

Monday, June 23, 2008

NASA's James E. Hansen will mark the

anniversary with new testimony.

(2004 Photo By Melanie Patterson --

Daily Iowan Via Ap)

There have been hotter days on Capitol Hill, but few where the heat itself became a kind of congressional exhibit. It was 98 degrees on June 23, 1988, and the warmth leaked in through the three big windows in Dirksen 366, overpowered the air conditioner, and left the crowd sweating and in shirt sleeves.

James E. Hansen, a NASA scientist, was testifying before the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee. He was planning to say something radical: Global warming was real, it was a threat, and it was already underway.

Hansen had hoped for a sweltering day to underscore his message.

"We were just lucky," Hansen said last week.

Today, 20 years later, a series of events around Washington will commemorate Hansen's appearance before the Senate committee. Hansen himself will appear before a House committee on global warming. [speech]

This anniversary comes just after a major setback for environmentalists, as a bill that would have begun to regulate greenhouse-gas emissions failed in the Senate.

But still, activists say that Hansen's 1988 testimony will look to history like a turning point -- a moment when the word "if" started to disappear from the national debate about climate change.

"Before Jim Hansen's testimony, global climate change was not on the political agenda. It was something that a few environmentalists and a few politicians . . . were talking about," said Jonathan Lash, president of the World Resources Institute, an environmental group.

"Hansen was clear, explicit and unequivocal," Lash said. "It absolutely put global climate change at the center of the discussion."

Hansen, the director of NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York, will give a speech on climate change at noon at the National Press Club. In the afternoon, he is scheduled to give a briefing before the House Select Committee on Energy Independence and Global Warming.

He is now semi-famous, at least in Washington, for his warnings about the growing danger of climate change -- and for his repeated showdowns with higher-ups who have sought control over his message. The clashes have been particularly frequent with the administration of George W. Bush.

In 1988, however, Hansen was just a government scientist, and his cause was almost equally obscure.

He told the sweltering senators that 1988 was shaping up to be the warmest year in recorded history, and that -- with heat-trapping gases building up in the atmosphere -- this was probably not a coincidence.

"The greenhouse effect has been detected, and it is changing our climate now," Hansen said, according to a Washington Post account of the hearing. "We already reached the point where the greenhouse effect is important."

Christopher Flavin of the Worldwatch Institute said Hansen's testimony made a crucial point: that rising temperatures were a problem for the present, not just for future generations.

"Until there was some evidence that it was actually happening, it was virtually impossible to motivate anyone," said Flavin, whose group is hosting Hansen's lunchtime speech today. "That will really sort of go down in history as a kind of pivot point."

Two decades later, climate change has become a global cause. Last year, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change -- a collaboration of scientists from around the world -- won the Nobel Peace Prize for research establishing a consensus that the phenomenon is real. The panel shared the prize with former vice president Al Gore, who was recognized for his film "An Inconvenient Truth."

But things look different on Capitol Hill. In the two decades since Hansen's testimony, Congress has not passed any law mandating major cuts in greenhouse-gas emissions. In that interval, 21 new coal-fired generating units have been built at power plants around the United States. The country's total emissions of carbon dioxide have climbed by about 18 percent, according to the latest statistics.

The most recent attempt to pass a law, sponsored by Sens. Joseph I. Lieberman (I-Conn.) and John W. Warner (R-Va.), was pulled from the Senate floor June 6, after its supporters could not muster the votes to overcome a filibuster threat.

Opponents of the bill said that it would impose huge costs on the U.S. economy by raising fuel prices and that it would deliver only uncertain results.

In an e-mailed statement, Sen. James M. Inhofe (R-Okla.) said the bill's failure was proof that Hansen's message had not caught on.

"Hansen, Gore, and the media have been trumpeting man-made climate doom since the 1980s. But Americans are not buying it," Inhofe said. "It's back to the drawing board for Hansen and company as the alleged 'consensus' over man-made climate fears continues to wane and more and more scientists declare their dissent."

Today, Hansen said, he intends to repeat his message from two decades ago -- this time with even more urgency. He said he believes that the United States must wean itself almost totally off fossil fuels, and do it as quickly as possible, to stave off the most catastrophic consequences of warming.

"We're at the situation again when there's this big gap between what we understand scientifically and what is known, recognized by the public and policymakers," he said. "This time, we have to close that gap in a hurry, because we're running out of time."

This time, though, the weather won't help as much. The high for today is supposed to be only in the low 80s.

Staff writer Joel Achenbach contributed to this report.

Put oil firm chiefs on trial, says leading climate change scientist

· Speech to US Congress will also criticise lobbyists

· 'Revolutionary' policies needed to tackle crisis

Ed Pilkington in New York

The Guardian,

Monday June 23, 2008

James Hansen, one of the world's leading climate scientists, will today call for the chief executives of large fossil fuel companies to be put on trial for high crimes against humanity and nature, accusing them of actively spreading doubt about global warming in the same way that tobacco companies blurred the links between smoking and cancer. [speech]

Hansen will use the symbolically charged 20th anniversary of his groundbreaking speech to the US Congress - in which he was among the first to sound the alarm over the reality of global warming - to argue that radical steps need to be taken immediately if the "perfect storm" of irreversible climate change is not to become inevitable.

Speaking before Congress again, he will accuse the chief executive officers of companies such as ExxonMobil and Peabody Energy of being fully aware of the disinformation about climate change they are spreading.

In an interview with the Guardian he said: "When you are in that kind of position, as the CEO of one the primary players who have been putting out misinformation even via organisations that affect what gets into school textbooks, then I think that's a crime."

He is also considering personally targeting members of Congress who have a poor track record on climate change in the coming November elections. He will campaign to have several of them unseated. Hansen's speech to Congress on June 23 1988 is seen as a seminal moment in bringing the threat of global warming to the public's attention. At a time when most scientists were still hesitant to speak out, he said the evidence of the greenhouse gas effect was 99% certain, adding "it is time to stop waffling".

He will tell the House select committee on energy independence and global warming this afternoon that he is now 99% certain that the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere has already risen beyond the safe level.

The current concentration is 385parts per million and is rising by 2ppm a year. Hansen, who heads Nasa's Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York, says 2009 will be a crucial year, with a new US president and talks on how to follow the Kyoto agreement.

He wants to see a moratorium on new coal-fired power plants, coupled with the creation of a huge grid of low-loss electric power lines buried under ground and spread across America, in order to give wind and solar power a chance of competing. "The new US president would have to take the initiative analogous to Kennedy's decision to go to the moon."

His sharpest words are reserved for the special interests he blames for public confusion about the nature of the global warming threat. "The problem is not political will, it's the alligator shoes - the lobbyists. It's the fact that money talks in Washington, and that democracy is not working the way it's intended to work."

A group seeking to increase pressure on international leaders is launching a campaign today called 350.org. It is taking out full-page adverts in papers such as the New York Times and the Swedish Falukuriren calling for the target level of CO2 to be lowered to 350ppm. The advert has been backed by 150 signatories, including Hansen

Canada tries to cool oil price anxiety

COMMENT: In this article, T. Boone Pickens is quoted: "... price is going to continue to rise until you kill demand." You don't need to be a market fundamentalist to understand the essential logic of this comment. On the other hand, the amazing price of oil today is hardly explainable just on supply-demand fundamentals. The Bye, Bubble? article from Barron's which I've sent out with this email, proposes that the price of oil may be significantly influenced by commodity investment and speculation - a "bubble", unsupported by fundamental conditions. It also notes that the high price of oil corresponds to high share prices for oil producers - and share prices will be the first to collapse if the price of oil collapses. Hmm.

Nothing should have advanced the climate change agenda more, and reduced fossil fuel use more effectively, than the recent screaming rise in oil prices. Had a carbon tax been applied around the world that had that effect on oil prices, the governments that created the taxes would have been unelected, juntad, couped, assassinated en masse. Yet the increase in the price of oil has not been accompanied with a corresponding reduction in global demand. Why is that? Inelasticities in the oil market? The Exxon Valdes effect - big things are slow to respond?

It suggests to me that carbon taxes, even whacking great ones, might not be as effective as we have hoped.

Shaun Polczer

Calgary Herald

Sunday, June 22, 2008

CALGARY - Canada is pushing for more transparency in global energy markets at a special meeting of producing countries in Saudi Arabia, Natural Resources Minister Gary Lunn said Sunday.

Speaking from Jeddah on Saudi Arabia's Red Sea coast, Lunn said Canada has a role to play in calming jittery oil prices that have more than doubled from a year ago.

"All of the countries recognize this is a longer-term problem," he said following the meeting of big oil oil majors and producing countries.

Although Canada accounts for less than three per cent of the world's oil production, it sits on 15 per cent of the world's reserves - second only to Saudi Arabia - mostly concentrated in northeast Alberta.

"It was recognized that there is an adequate supply of oil reserves that remain for decades to come, but we do need to make strategic investments in development of some of these reserves as well as refining capacity."

Despite its relatively small share of the world oil market, Lunn noted that Canada is one of the few countries capable of significantly increasing production.

The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers said last week Canada's output will nearly double to 4.5 million barrels per day by 2020. More than $100 billion worth of investments are on the books to triple oilsands production which is currently supplying slightly more than one million barrels per day.

Lunn described a "very co-operative approach" at the meeting, which committed to increasing oil production in a manner that recognizes the impact on the environment.

At the meeting, the Saudis suggested they would increase production over and above the 200,000 barrels per day they pledged last week.

But speaking in Calgary Friday, legendary Texas oil man T. Boone Pickens called the Saudi's additional production "peanuts" and said at least world two million additional barrels per day are needed to make a meaningful dent in oil prices.

He said blaming speculators for higher prices is "silly" and told the U.S. Senate last week that global oil production has peaked at 85 million barrels per day.

"So, what is going to happen is that price is going to continue to rise until you kill demand."

Earlier Sunday, King Abdullah said Saudi Arabia is not to blame for soaring oil prices, blaming speculators and surging demand in such developing economies as China and India.

"There are several factors behind the unjustified, swift rise in oil prices and they are: Speculators who play the market out of selfish interests, increased consumption by several developing economies and additional taxes on oil in several consuming countries," the king said in speech.

Despite their best intentions, doubts lingered as to whether the meeting will have an impact on oil prices.

"What I've heard so far are basically all good ideas, but it will probably not change the price tomorrow morning," Royal Dutch Shell CEO Jeroen van der Veer told Reuters in Jeddah.

Energy Minister Mel Knight of Alberta Friday told the Illinois Chamber of Commerce on Friday he expects oil prices to "spike" to $200 and said anything over $150 would damage the world economy.

Gerry Protti, an executive vice-president with Calgary-based EnCana Corp., also doubted whether the Jeddah meeting would accomplish its stated goal of lowering oil prices.

Speaking at the company's investor day on Thursday, Protti said Canada is a "price taker" rather than a "price setter" in the world market. He also said Canada is a marginal player despite its position as the number one supplier of oil and products to the United States.

"It's a market driven by huge forces, of which Canada, from a supply side, is one relatively small component."

There is also the question of whether lower oil prices are actually good for Canada and could threaten the economic viability of oilsands production.

Canada has consistently been pegged as one of the planet's highest-cost suppliers by advisory firms such as J.S. Herold in Connecticut.

Oilsands producers like Canadian Natural Resources' Steve Laut have said the company needs at least $75 US a barrel to cover costs and generate "acceptable" rates of return.

Speaking at the OPEC summit in November, Saudi oil minister Ali al-Naimi said Canada's "sands of oil" rely on unsustainable oil prices to be economically viable.

spolczer@theherald.canwest.com

© Calgary Herald 2008

Bye, Bubble? The Price of Oil May Be Peaking

Andrew Bary

Barron's

June 23, 2008

IT'S PERILOUS TO CALL THE TOP IN A BOOMING MARKET, but the price of oil may be peaking in the current range of $130 to $140 a barrel.

Oil's sharp move up -- prices have doubled in the past year -- caught the world by surprise, including almost everyone involved in the petroleum market, from major exporting nations to big energy companies to the global analyst community. The rally has emboldened oil bulls, who argue the world is bumping up against oil-supply constraints, and that demand will rise inexorably, despite sharply higher prices, as the four billion to five billion people in emerging economies like China and India get a taste of the energy-intensive good life, replete with the cars, air conditioners, refrigerators and computers that Americans and Western Europeans have long enjoyed. Statistics support their view that demand growth is in its infancy in the developing world: U.S. per-capita oil consumption is 25 barrels annually, while Japan uses 14 barrels per person. China's 1.3 billion people consume just two barrels each per year, however, and India's 1.1 billion use less than a barrel a year.

In the next decade, oil indeed may hit $200 a barrel. But prices could fall to $100 a barrel by the end of this year if Saudi Arabia makes good on its pledge to increase production; global demand eases; the Federal Reserve begins lifting short-term interest rates; the dollar rallies, and investors stop pouring money into the oil market. China raised prices on retail gasoline and diesel fuel by 18% Thursday, in a move that is expected to curb demand.

It's tough to know how much of the surge in crude-oil prices -- up 40% just this year -- reflects fundamental supply and demand, and how much is due to other factors, including the dollar, commodity speculation and interest from institutional investors. Like some others, we suspect the run-up was fueled by more than economics.

Jason Edmiston

THERE IS GROWING TALK OF AN OIL BUBBLE, THOUGH evidence of asset bubbles isn't conclusive until they burst. The trajectory of oil prices in the past eight years looks eerily similar to the Nasdaq's eight-year run to a peak of more than 5,000 in March 2000. More than eight years later, the Nasdaq is at half that level.

"My basic message to those who say that prices have to go up forever is that the oil markets have been cyclical for 140 years. Why should that have stopped?" says Edward Morse, chief energy economist at Lehman Brothers.

Saudi Arabia, the world's biggest oil exporter, has pledged to boost production from a recent 9.5 million barrels a day to about 9.7 million in order to reduce prices. The Saudis are hosting a summit of oil producers and consumers on June 22.

"The analytic community is divided on what the recent Saudi comments mean for the market," says Morse, who believes the Saudis will put more oil on the market as they raise production. "That, combined with a declining rate of consumption, should create an inventory surplus that will be palpable as the year progresses."

Morse thinks oil could fall to $100 by year end.

Skeptics say the Saudi vow to boost production is merely talk, and that the country is struggling simply to maintain production because of aging, overworked fields like the huge, 60-year-old Ghawar reservoir. The Saudi government refuses to allow in outsiders to evaluate the state of its oil industry, which has fueled talk the Saudis are hiding something.

Likewise, the size of speculative positions and commodity indexers is impossible to determine, as most trading occurs away from the major commodity exchanges in over-the-counter transactions.

It is hard to argue that oil demand supports $135 crude. Now at 86 million barrels a day, global demand could show little or no increase this year after averaging 1% gains in recent years. Sanford Bernstein analyst Neil McMahon projects that by the fourth quarter, global oil demand could be running below the fourth quarter of 2007.

Consumption is down in '08 in the 30 member nations of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which includes the U.S., Western Europe, Japan and Australia. OECD nations account for 57% of global oil demand.

While Americans are married to their cars, $4-a-gallon gasoline has begun to bite; the number of vehicle miles traveled in the U.S fell in March on a year-over-year basis for the first time since 1979. Further declines in gasoline consumption may follow as drivers opt for more fuel-efficient cars, and as innovations like plug-in cars reach the market after 2010. Major U.S. airlines have announced widespread capacity reductions, which could cut demand for jet fuel by 5% or more later this year.

Oil demand continues to grow in the developing world and the Middle East. In Europe, stiff energy taxes generally blunt the impact of higher prices, but diesel fuel, now at nearly $10 a gallon in Britain (double the American price), may be at an unsupportable level. Demand growth could cool in emerging markets, too, as subsidies in many Asian countries are reduced. There is also speculation China has been hoarding diesel fuel ahead of the Olympics in August, in order to cut the use of coal for power generation around Beijing in the hope of cleaning up the city's notoriously polluted air. Once the games are over, China will go back to burning cheaper coal, the story goes.

The supply/demand argument for higher oil prices has some merit. "Name another commodity that has gone up two-and-a-half times in three-and-a-half years and the world hasn't found a way to make more of it," says Byron Wien, chief investment strategist at Pequot Capital Management. "The world isn't finding oil fast enough to replace the 3% to 4% that gets pumped every year."

Wien's boss, Art Samberg, who heads the Westport, Conn.-based investment firm, stated in Barron's midyear Roundtable, published last week, that the commodity bubble "isn't going to burst. It's going to continue to expand." Older oil fields in Mexico and the North Sea are running dry while new sources in places like Kazakhstan and Brazil may prove difficult to bring on stream. In addition, oil increasingly is in the hands of government-run monopolies that may be more interested in maximizing future revenue than boosting current production.

Attachment: An Oil Overview

The dollar's slide and the Federal Reserve's neglect of the greenback have supported commodity prices, oil in particular. But Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke and his colleagues finally seem to have realized that the Fed's aggressive easing actions since last summer, which dropped the key federal-funds rate to 2% from 5.25%, may be fueling global inflation. If the Fed moves to lift rates later this year, as financial markets anticipate, it could buttress the dollar and spur an exodus of speculators from the oil market.

One little-discussed way the U.S. could try to bring down oil prices is to sell oil from the strategic petroleum reserve (SPR). The SPR, intended as a source of oil for national emergencies, now holds 705 million barrels of crude, equal to about 35 days of domestic consumption. With prices higher, Congress moved in May to stop adding to the SPR as it neared capacity. A sale of 100 million barrels of oil would shock the markets and potentially drive down prices.

Long term, the U.S. could benefit through lower oil prices if Congress and the states back President Bush's proposal to allow drilling off Florida, the East and West coasts, and in the Alaskan National Wildlife Reserve, where billions of barrels of oil may lie.

A SHARP DROP IN ENERGY PRICES WOULD HELP WHOLE swaths of the U.S. economy, including retailers, food and household-goods makers, auto makers and transportation concerns. Beleaguered U.S. airlines would benefit because they're expected to spend $61 billion on fuel this year, up $20 billion from 2007.

Few oil stocks would be safe if crude falls $20 to $30 a barrel. Independent exploration and production companies like Devon Energy (DVN), Apache (APA) and XTO Energy (XTO) could get hit hard because they're up sharply in the past year. The majors, including ExxonMobil (XOM), Chevron (CVX) and ConocoPhillips (COP), might hold up better because they have refining and related businesses like chemicals, whose profitability isn't directly linked to crude and natural-gas prices.

Some of the biggest oil companies, notably ExxonMobil, Royal Dutch Shell (RDS/A) and BP (BP), have badly lagged in the past year. BP, for one, has been beset by problems, including a troubled joint venture in Russia.

The majors may be the best energy values because they trade for less than 10 times this year's earnings and around eight times estimated 2009 profits. The '09 earnings consensus reflects an assumption of $100 crude, not the current $135. Bernstein's McMahon estimates Exxon could earn $12 share in 2009, versus the current consensus of $9, if oil holds $130 and natural gas averages $11 per thousand cubic feet; it is now around $13. This suggests Exxon, at 86, may be trading for just seven times estimated '09 profits. Conoco and Chevron also could earn far more than the current '09 consensus under the same oil and gas scenario, Bernstein estimates. McMahon favors BP, Royal Dutch and Marathon Oil (MRO).

One reason for the strength in crude has been modest U.S. inventories. Bill Klesse, chief executive of Valero Energy (VLO), the largest North American oil refiner, told analysts last month that the inventory data may be misinterpreted as a sign of oil scarcity, though it is more a function of the recent state of the oil market, in which futures prices were below spot prices, giving refiners little incentive to maintain excess supply. If the Saudis sell enough oil to drive down spot prices relative to futures prices, refiners and others will be induced to buy and hold more oil in inventory, he said. The oil market is moving to such a configuration, with the current, or spot price of $135 below the December 2008 price of $136.

OIL-MARKET EXPERTS ACKNOWLEDGE THAT commodity-indexing strategies employed by endowments, pension funds and other institutional investors have helped push up prices in the past year. Such investments are thought to have totaled $260 billion as of March, up from $13 billion at the end of 2003, according to Michael Masters, the head of Masters Capital Management, an Atlanta investment firm. Some $55 billion may have flowed into commodity investments during the first quarter alone. The energy complex is the largest commodity market, and gets a disproportionate share of fund flows. Masters estimates index participants may control over 1 billion barrels of crude.

Managers of leading university endowments, including those at Harvard, Yale and Princeton, in recent years have generated outsized returns from investments in hard assets, prompting other investors, such as the giant California Public Employees Retirement System, with over $200 billion in assets, to attempt the same. Calpers is upping its commodity exposure to $7 billion from under $500 million.

This activity is spurring a backlash in Congress, where pension funds and others have been accused of driving up food and energy costs through their increased commodity investments. Lawmakers including Senator Joe Lieberman (independent, Conn.) have proposed a ban on commodity-related investments by pension funds, which Masters supports. Last month he told Congress that commodity regulators need to close a loophole that lets indexers evade commodity-position limits by purchasing over-the-counter swaps and other derivatives.

A selloff in oil and other commodities could cool the ardor for index strategies. Ross Margolies, head of Stelliam Investment Management, in New York, says financial investors would do better buying the shares of commodities producers, not actual goods. Over time, it may be more difficult to make money in commodity investing because holders effectively incur financial costs to carry and store commodities, even if they never take physical delivery.

Though little noticed, short-covering by independent oil and gas producers might have contributed to the recent strength in oil and gas prices. U.S. exploration and production companies like Devon, XTO and Chesapeake Energy (CHK) have hedged an average of about 40% of their 2008 production by selling oil and gas futures, options or derivatives, according to Credit Suisse analyst Jonathan Wolff. As prices have surged, the hedges have slipped underwater, and some producers have sought to unwind their money-losing bets.

Newfield Exploration (NFX) recently announced a $500 million hedge-related loss, and more red ink could follow. Total hedge losses among E&P companies could top $15 billion for 2008, and $8 billion for 2009, Wolff estimates.

While supply challenges could continue to dog the oil market, current prices seem excessive in light of weakening demand and other factors. But it's impossible to know with precision when the bubble will burst. The Saudis could roil the markets with a pronouncement June 22; the dollar could revive or demand could plummet, or all three. And if prices start falling, the downturn could accelerate, sending crude back to $100 -- where it would be cheaper, but still far from cheap.

E-mail comments to mail@barrons.com

June 22, 2008

A Green Coal Baron?

Photograph by John Foxx/Getty Images; Illustration by Geoff McFetridge

THE INVISIBLE HAND ON THE SCALES: In a cap-and-trade system, the government caps the amount of carbon dioxide that energy companies can emit. Then it distributes a new kind of currency — carbon allowances — that each firm must possess to be allowed to release their CO2. If Utility A figures out how to reduce its emissions faster than required — by using cleaner fuels, say, or investing in meliorative technologies — it can trade (sell) its unused allowances to Utility B. The cap is lowered regularly, and because market forces reward those that make the biggest cuts, the system should produce a race to see whose carbon footprint can shrink the fastest.

By CLIVE THOMPSON

New York Times

June 22, 2008