Curbing Emissions by Sealing Gas Leaks

COMMENT: 30% of atmospheric methane comes from the production, processing, storage and movement of fossil fuels. It comes from equipment leaks, venting and flaring, evaporation losses, disposal of waste gas streams, and accidents and equipment failures.

In British Columbia, with relatively low oil production, virtually all methane emissions come from natural gas production.

BC’s natural gas industry could be responsible for up to half a million tonnes (MT) of methane annually.

That’s NOT a half million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e). At the 100 year greenhouse intensity figure of 25 the methane represents 12.5 MT of carbon dioxide. At the more realistic 20 year intensity of 72, it is 36 MT of CO2e – more than half the provincial GHG total of 66 MT.

Enough gas escapes that it begs the question – isn't the cost of arresting the fugitive gas less than the value of the lost gas? This article suggests so. Perhaps it doesn't matter, since a policy decision by the provincial government, backed up with appropriate penalties, could ensure that it is a good bottom line decision for industry to put an end to fugitive methane.*

*These comments are taken from an unpublished Watershed Sentinel article on fugitive methane emissions

By ANDREW C. REVKIN and CLIFFORD KRAUSS

New York Times

October 14, 2009

To the naked eye, no emissions from an oil storage tank are visible. But viewed with an infrared lens, escaping methane is evident. (Photographs by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency) |

To the naked eye, there was nothing to be seen at a natural gas well in eastern Texas but beige pipes and tanks baking in the sun.

But in the viewfinder of Terry Gosney’s infrared camera, three black plumes of gas gushed through leaks that were otherwise invisible.

Terry Gosney uses an infrared camera to check for leaks in natural gas pipes in eastern Texas. (Scott Dalton for The New York Times) |

“Holy smoke, it’s blowing like mad,” said Mr. Gosney, an environmental field coordinator for EnCana, the Canadian gas producer that operates the year-old well near Franklin, Tex. “It does look nasty.”

Within a few days the leaks had been sealed by workers.

Efforts like EnCana’s save energy and money. Yet they are also a cheap, effective way of blunting climate change that could potentially be replicated thousands of times over, from Wyoming to Siberia, energy experts say. Natural gas consists almost entirely of methane, a potent heat-trapping gas that scientists say accounts for as much as a third of the human contribution to global warming.

“This for me is an absolute no-brainer, even more so than putting in those compact fluorescent bulbs in your house,” said Al Armendariz, an engineer at Southern Methodist University who studies pollutants from oil and gas fields.

Acting quickly to stanch the loss of methane could substantially cut warming in the short run, even as countries tackle the tougher challenge of cutting the dominant greenhouse emission, carbon dioxide, studies by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology suggest.

Unlike carbon dioxide, which can remain in the atmosphere a century or more once released, methane persists in the air for about 10 years. So aggressively reining in emissions now would mean that far less of the gas would be warming the earth in a decade or so.

Methane is also a valuable target because while it is far rarer and more fleeting than carbon dioxide, ton for ton, it traps 25 times as much heat, researchers say.

Yet while federal and international programs have encouraged companies to seek and curb methane emissions from gas and oil wells, pipelines and tanks, aggressive efforts like EnCana’s are still far from the industry norm.

|

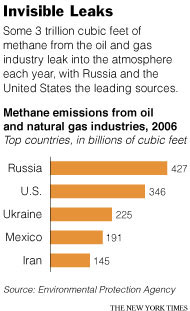

As a result, some three trillion cubic feet of methane leak into the air every year, with Russia and the United States the leading sources, according to the Environmental Protection Agency’s official estimate. (This amount has the warming power of emissions from over half the coal plants in the United States.) And government scientists and industry officials caution that the real figure is almost certainly higher.

Unless monitoring is greatly expanded, they say, such emissions could soar as global production of natural gas increases over the next few decades.

The Energy Department projects that gas production could rise nearly 50 percent over the next 20 years as companies race to discover and tap new sources. In the United States, 4,000 miles of new pipeline was laid last year alone.

But the industry has been largely resistant to an aggressive cleanup.

The Bush administration, which opposed mandatory limits on greenhouse gas emissions, expanded an existing voluntary domestic program for capturing methane emissions and began a related international program — with both aimed at promoting profitable ways for businesses to cut methane emissions as a relatively easy first step to combat climate change.

In April the Obama administration signaled that it could adopt rules requiring the biggest American companies to report all of their greenhouse gas emissions. Oil and gas industry groups countered that the cost and complexity of dealing with some 700,000 wells were too great.

In September the E.P.A. announced that the obligatory reporting would begin in 2011 but that it excluded oil and gas operations, at least for the time being. (Agency officials say they plan to issue rules for oil and gas by late next year.)

Some scientists reject the industry arguments. “Further delay on finding and stopping such releases would be irresponsible, given the financial and environmental benefits,” said F. Sherwood Rowland, a Nobel laureate in chemistry at the University of California, Irvine.

Internationally, the amount of methane escaping from gas and oil operations can be only crudely gauged. But in 2006 the E.P.A. estimated that Russia, the world’s largest gas producer, ranked highest, with 427 billion cubic feet of methane escaping annually, followed by the United States at 346 billion, Ukraine at 225 billion and Mexico at 191 billion.

Reflecting the uncertainty in such estimates, Gazprom, Russia’s giant state gas monopoly, estimated its annual emissions at half that figure last year.

An E.P.A. review of methane emissions from gas wells in the United States strongly implies that all of these figures may be too low. In its analysis, the E.P.A. concluded that the amount emitted by routine operations at gas wells — not including leaks like those seen near Franklin — is 12 times the agency’s longtime estimate of nine billion cubic feet. In heat-trapping potential, that new estimate equals the carbon dioxide emitted annually by eight million cars.

In the routine operations, great yet invisible plumes of gas enter the atmosphere when new wells are activated, old wells are invigorated to boost gas flows and wells are purged of fluids by letting out cough-like bursts of gas.

In many gas fields, said Roger Fernandez, a senior methane expert at the E.P.A., fluid-clogged wells are still purged the old-fashioned way, by opening valves or using outdated equipment in ways that release a misty burst of gas directly into the air.

For the E.P.A. and environmental scientists, the challenge is convincing gas and oil producers here and abroad that efforts to avoid such releases often more than pay for themselves.

The use of infrared cameras is expanding as word spreads of the payoff in saved gas, said Ben Shepperd, executive vice president of the Permian Basin Petroleum Association, which represents 1,200 companies in the oil and gas business around West Texas.

“We would like to see more people doing it,” he said. “People are very surprised when they shoot their equipment with these cameras and they see that there are releases in places they wouldn’t have expected.”

The benefits are there not only for gas producers but also for companies handling oil. Thousands of oil storage tanks emit plumes of methane and other gases, said Larry S. Richards, the president of Hy-Bon Engineering in Midland, Tex., which is using infrared cameras to survey storage tanks in 29 countries and sells systems that capture the gas.

A clearer view of the worst methane emissions could come next year, when Japan plans to start releasing data from Gosat, a satellite that began orbiting the Earth in January. It may be able to identify the top hot spots within a few miles.

That may increase pressure on countries with particularly large leaks.

As the biggest methane emitter, Russia has begun seeking high-tech solutions. In April, for example, Gazprom, the Russian Defense Ministry and an Israeli aerospace company began discussing the potential use of miniature remotely piloted helicopters to monitor pipelines for leaks.

But gadgets alone will not halt the vast exhalation of methane from Russia, environmentalists say. There is some hope that a successor to the 1997 Kyoto climate change pact will include more incentives for money to flow to Russian methane-reduction projects.

Western companies that have captured methane point out the money that is often to be made by doing so.

Starting around 2000, BP began introducing methane-catching techniques at 2,300 well sites in New Mexico. At well after well, gas that would have otherwise escaped now flows through meters that field crews affectionately call the “cash register.”

Among other actions, BP engineers have fine-tuned a system for purging fluids that can stop up wells. The process uses the pressure of gas in the well to periodically raise a plunger through the vertical well pipe. This removes the liquids but typically allows gas to escape.

The new computerized process, which BP calls smart automation, tracks well pressure and other conditions to more precisely time the plunger cycles in ways that avoid gas emissions. From 2000 to 2004, emissions from BP wells in the region dropped 50 percent, the company says. By 2007, they had essentially ended.

On average, installing the systems has cost about $11,000 per well, but they have returned three times that investment, said Reid Smith, an environmental adviser for BP working on the project.

“We spend a lot of money to get gas to the surface,” Mr. Smith said. “It makes a huge amount of sense to get all of it through the sales meter.”

Andrew C. Revkin reported from New York and Farmington, N.M., and Clifford Krauss from Franklin, Tex. Andrew E. Kramer contributed reporting from Moscow.

Posted by Arthur Caldicott on 16 Oct 2009