Lineup for LNG project adds a competitor

by Ted Sickinger

The Oregonian

Monday October 13, 2008

Peter Hansen, chief executive of Oregon LNG, has spent nearly five years pushing a proposal to build a liquefied natural gas terminal on the Skipanon peninsula, just west of Astoria (in background). His company filed a formal application Friday with federal energy regulators. |

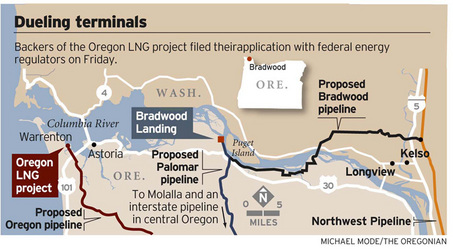

Most controversy over liquefied natural gas in Oregon has focused on proposals to build an import terminal 20 miles east of Astoria on the Columbia River and on a competing project in Coos Bay.

With little fanfare Friday, however, backers of a third LNG project delivered 21 binders to federal energy regulators containing their application to build a terminal on a spit of sand and blackberry brambles that juts into the Columbia River from Warrenton.

Oregon LNG, as the company is called, isn't exactly new. The project was launched in 2004 by Calpine Corp., which went into bankruptcy a year later. Managers of the project kept pushing local land-use approvals for the terminal, and later bought out Calpine with backing from a New York-based holding company, Leucadia National Corp., that specializes in distressed investments.

Their plan is to erect three mammoth gas-storage tanks on the Skipanon peninsula, each 17 stories tall, almost as wide as a football field and highly visible from Astoria, which is directly across Young's Bay from the project site.

The gas-receiving terminal would be coupled to a pier sticking 2,100 feet into the Columbia, where a new generation of LNG supertankers would dock in a dredged basin to unload their cargoes.

|

The $1 billion terminal would be capable of importing a billion cubic feet of natural gas a day - almost twice Oregon's daily consumption. The gas would be shipped to markets throughout the Northwest and California via "the Oregon pipeline." The 36-inch, high-pressure line is slated to arc through 121 miles of farm- and forestland in Clatsop, Tillamook, Washington, Yamhill, Marion and Clackamas counties to a gas hub in Molalla.

Oregon LNG's application comes as the U.S. market for gas appears to have temporarily collapsed. Domestically produced gas is cheap and abundant. Asian countries are willing to pay such eye-popping premiums for LNG cargoes that many industry experts doubt it makes sense to import LNG to the United States.

Industry giants are sending the same message. British Petroleum recently backed out of a proposed terminal on the Delaware River, citing lousy industry conditions, while several terminals are applying for permission to export U.S. and Canadian gas to take advantage of the Asian bonanza.

Moreover, just as the Houston-based backers of the Bradwood Landing LNG proposal have met vehement opposition, local landowners, environmentalists and tribal groups could put up a stiff fight against Oregon LNG.

"We're opposed," said Brent Foster, executive director of Columbia Riverkeeper. "It would have a massive impact on the Columbia estuary. It comes with a significant pipeline that would impact farms, forestlands and rivers. And it's right in the middle of the flight path to the Astoria airport.

"There's no way you can call this a good site."

Oregon LNG executives obviously disagree. They figure their chances of commercial success are good enough to justify investing tens of millions of dollars in a labyrinthine permitting process.

Oregon LNG Chief Executive Peter Hansen said his aim is to build collaborative relationships and open dialogues - even with his opponents. The approach has built credibility and some good will among state regulators, tribal groups and environmental opponents.

Julie Carter, a lawyer with the Columbia River Intertribal Fish Commission, said the jury is still out on how the tribes will react to the project, which they still consider a huge industrial development on the river. But she said the company's approach has been refreshing.

"We've been pleased with the way they've been treating our interests and concerns, and how they've carried on this process," Carter said.

Hansen said Oregon LNG has spent $20 million and will continue spending $1.5 million a month to resolve myriad environmental, engineering and safety questions. This summer, for example, the company had biologists in the Tillamook forest hooting like spotted owls to determine whether its pipeline would harm owl habitat. It has done similar surveys for marbled murrelets and rare native plants.

"You can give agencies what they want today or fight them for two years, then give them what they want," Hansen said. "In the end, the issues are what they are, and you're the only one in any kind of a hurry."

As far as gas supply goes, Hansen says producers will more than double the supply of LNG on world markets by 2015, freeing up cargoes to come to the United States at competitive prices.

"There's a lot of interest in having a bridgehead to the U.S. market on the West Coast," he said. "From a producer's perspective, this is a pretty cheap option."

Hansen, a Dane who has traipsed around the globe as an energy industry engineer, has spent the past five years on the Oregon LNG project, first as an executive with Calpine Corp. When that company went bankrupt, he continued pursuing the project and later led a management buyout from Calpine.

Lately, his quest has become something of a knife fight with the backers of the Bradwood Landing LNG project, upriver from Astoria. Backers of the projects always have been competitive, but that competition has become more hostile recently, with each trying to scuttle or at least slow the other's regulatory approvals.

Hansen contends his Warrenton site is far superior to Bradwood. From an environmental standpoint, there's simply far less fish habitat to harm off the Skipanon peninsula, he contends. And he pulls no punches in discussing what he perceives as Bradwood's major flaw.

"Why would you bring an LNG tanker under the Astoria bridge?" Hansen said. "A pool fire is like a nuclear meltdown. The likelihood of such an accident is remote, but the consequence is enormous. ... It would burn Astoria."

If it's OK to bring LNG to Bradwood, Hansen asked, then why not put a terminal much farther upriver - say, in Kalama or Portland? The answer, he said, is plain common sense: "Let's not take that risk," he said.

Bradwood's backer, Houston-based NorthernStar Natural Gas Inc., counters that Oregon LNG sits on an unstable sand spit in the middle of earthquake and tsunami zones. The site is too close to Astoria's airport, NorthernStar executives say — one reason they rejected it in their early research.

Moreover, NorthernStar contends it has acquired an ownership interest in the Skipanon peninsula site. It has asked regulators to stop processing Oregon LNG's application and has indicated that it intends to take a spoiler role in any land-use changes that Oregon LNG seeks.

The back and forth between the companies is likely to continue. Both have invested heavily in their projects, and both say only one terminal ever will be built. Though NorthernStar already has federal approval and is seeking to win state permits sometime in early 2009, Hansen said that's wildly optimistic and that he still thinks he can beat his rival to the regulatory finish line.

Ted Sickinger; tedsickinger@news.oregonian.com

Posted by Arthur Caldicott on 15 Oct 2008