Wind: The Power. The Promise. The Business

A partial answer to America's energy crisis is springing up. But the struggle to harness the winds of Kansas shows the difficulty in building an industry that threatens the status quo

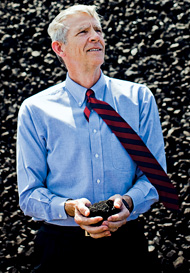

Wind evangelist: Pete Ferrell on his 7,000-acre ranch in southeastern Kansas Bob Stefko

by Steve Hamm

Business Week

3 July 2008

It's an ordinary day on Pete Ferrell's 7,000-acre ranch in the Flint Hills of southeastern Kansas. Meaning, it's really windy. When he drives his silver Toyota Tundra out of the canyon where the ranch buildings nestle, the truck rocks from the gusts. Up on top of a ridge, surrounded by a sweeping vista of low hills, rippling grass, and towering wind turbines that make you feel like a mouse scampering underfoot, Ferrell carefully navigates into a spot where the wind won't damage the doors when they're opened. Then he points to an old-style windmill, used for pumping water, which was erected by his father decades earlier when the ranch was in the throes of a drought. "That's the windmill that saved us in the '30s," he explains, his voice growing husky with emotion.

Windmills on the high plains have raised

the ire of prairie preservationists Bob Stefko

Ferrell, 55, is a fourth-generation Kansan who looks the part. He's slim with gray hair, squint-lines, and a cowboy hat. His great-grandfather established Ferrell Ranch on the high plains east of Wichita in 1888, and it has nearly failed several times over the years. Ferrell has held the place together through cattle grazing, oil wells, and, now, wind. He owns the land under 50 of the 100 turbines of the Elk River Wind Project, a 150-megawatt wind farm that opened in 2005.

Ferrell is one of the fathers of Kansas wind farming. He ran through three different developers before getting the operation going on his land. There was stiff opposition to wind farming in the Flint Hills from preservationists concerned about marring the landscape and from politicians tied to the coal industry, but, finally, Ferrell had his way. He now travels the state as an evangelist. "He has been a great spokesman for wind in Kansas," says Mark Lawlor, project manager in the state for Horizon Wind Energy, a wind farm developer. "He has lived off the land, and he's found something new he can tap into."

For centuries, the wind has been the enemy of the farmer. It blows away soil, dries out crops, and the howling makes some people crazy. So it's a twist of fate that wind is now emerging as an ally. Some call the vast American prairie the Saudi Arabia of wind, capable of producing enough electricity to meet the entire country's needs—assuming there's the will to harness it.

Wind power, while still just a speck in America's total energy mix, is no longer some fantasy of the Birkenstock set. In the U.S., more than 25,000 turbines produce 17 gigawatts of electricity-generating capacity, enough to power 4.5 million homes. Total capacity rose 45% last year and is forecast to nearly triple by 2012. Right now, only 1% of the country's electricity comes from wind, but government and industry leaders want to see that share hit 20% by 2030, both to boost the supply of carbon-free energy and to create green-collar jobs.

Such a transformation won't come easily. While much of America's wind energy is in the Midwest, demand for electricity is on the coasts. And the electrical grid, designed decades ago, can't move large quantities of electricity thousands of miles. There's plenty of wind off the coasts, but it's both expensive to harness and controversial; not-in-my-backyard sentiment has slowed some of the most high-profile projects.

Kansas, in the middle of the wind belt, has become a battleground for the wind revolution. Advocates of alternative energy are pitted against defenders of the status quo, which in Kansas means coal. The flash point: a proposal by Sunflower Electric Power to build two 700-megawatt, coal-fired power plants in western Kansas. State regulators denied permits on the basis of CO2 emissions, the Republican-controlled legislature passed bills to overturn the ruling, Democratic Governor Kathleen Sebelius vetoed the bills, and the legislature has narrowly sustained her vetoes. So ferocious is this fight that Sunflower and its allies placed ads in newspapers suggesting that because Sebelius is against their coal project she's playing into the hands of Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. The poisoned atmosphere helps explain why Kansas has only 364megawatts of wind power capacity from about 300 turbines, despite having some of the hardest-blowing wind in the country, while Texas produces more than 10 times as much.

ELECTRICITY HIGHWAY

Making matters worse, Kansas has a poor electrical transmission grid. Most of the coal-fired plants are clustered around Kansas City in the east, yet most of the wind energy is on the thinly populated plains to the west. Now, emboldened by Sebelius' interest in wind energy, independent transmission outfits are lining up to build high-capacity lines from the windy west to consumers not only within the state but also beyond its borders. The U.S. Energy Dept., among others, would like to build the equivalent of an interstate highway system for transporting electricity around the country—if it could only find a budget for it.

The part of the project targeting wind alone would cost about $20 billion. Another hang-up: Major new transmission projects take up to four years to get approval from municipalities and state utility authorities. "The process just doesn't work," says Joseph L. Welch, chief executive of ITC Holdings, a Michigan-based transmission company that hopes to build a major line through wind country.

Ferrell, in trying to save his family spread,

became an early advocate of wind farming

Bob Stefko

The struggles to get wind projects going weigh on Ferrell's mind as he drives west on Route 96 through Wichita, Hutchinson, Great Bend, and the smaller towns of Albert, Timken, and Rush Center. Ferrell is on his way to tiny Bazine, a community in Ness County 208 miles from his home, to talk to landowners who have banded together to attract a wind farm developer. This is his new gig. He travels the state advising locals on how to get projects going, sometimes collecting consulting fees from landowners. He also is working with partners who have money to develop his own projects. "I learned my lessons in the Flint Hills. [Wind opponents] beat me up good. Now I know how to get things done," says Ferrell.

In Great Bend, Ferrell passes a gas-fired power plant operated by Sunflower. Running a utility company isn't simple. Since electricity can't be stored cheaply, you have to match supply and demand. Typically, that's done with a combination of low-cost coal and nuclear power, gas plants like this one that can be started quickly, and wind and other alternatives. Wind blows harder at some times than others, so you can't depend on a steady supply—though that may change in a few years if there are enough wind farms in different places.

Coal, for the most part, is a cheaper alternative. It costs Sunflower about 1.5 cents per kilowatt-hour to produce electricity at coal plants, 10 cents to 14 cents in gas plants, and 4.5 cents for the electricity it buys from wind farms. But the economics of energy are changing fast. Coal prices have doubled in a year. And if you compare the costs of coal from new plants with wind energy from new wind farms, taking into account capital costs, they're roughly comparable, according to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, which is funded by the Energy Dept.

"BATTLEGROUND" FOR THE NATION

Sunflower’'s Watkins has met stiff opposition

trying to build two giant coal plants

Bob Stefko

Still, Sunflower hopes to forge ahead with its new coal plants, with a victory either in the legislature or the courts. Earl Watkins, its chief executive, complains that Kansas didn't have the right to deny permits because CO2 emissions are not specifically cited in the regulations. "It's like being pulled over and ticketed by a policeman for running a stop sign—and there's no stop sign there," he says.

This point will be debated in legislatures and courtrooms across the land over the coming years. "We have become a battleground for the whole nation," says Lieutenant Governor Mark Parkinson, a Democrat, who has spearheaded Kansas' energy initiatives. CO2, which has been linked to global warming, is not covered by most environmental rules. Yet other states are turning down coal plant permits for the same reasons Kansas did. In fact, wind power advocates argue that if the cost to the environment and the economy of CO2 emissions were included when comparing the expense of running coal plants vs. wind farms, wind would be cheaper.

In Bazine, a town with a smattering of houses, Ferrell pulls up in front of the Golden Years Senior Center. It's a single-story metal building on the edge of a cornfield. Inside, he helps rough-handed farmers set up folding chairs, and soon most seats are filled. Ferrell gives a primer on wind. Landowners typically get about $2,000 per turbine per year, but he advises them to stick together to gain negotiating strength on price. Also, they should own a piece of the project, not just collect lease royalties. He adds he'd be willing to develop their project or be a consultant.

Meetings like this are happening all over Kansas. More than a dozen projects are on the drawing board, and a slew of wind farm developers are aggressively mapping out the plains and ridgelines looking for the best locations for turbines. In some cases, they attempt to cut secret deals, giving different landowners different prices. That tends to anger the locals and is why the folks in Ness County decided to unite. "There's a wind rush going on out here," says Terry Antenen, who is one of the organizers. "Instead of being picked off, we're going out and picking our developer." He says he trusts Ferrell for advice more than he would an outsider.

On Ferrell's drive home from Bazine, the night sky is lit up with Kansas fireworks—huge lightning strikes. Thanks to the wind farm fees, he says, he has been paying off mortgages on his land. Now he has tied up with Tom Rinehart, a natural gas entrepreneur, to develop wind farms. In time, he hopes to hand off the Ferrell Ranch to his two children, now in college. And if things go really well, he says, he'll set up a foundation dedicated to community development within the Flint Hills.

HELP FROM WASHINGTON

He's sensitive about prairie protection issues. Some former friends in the Flint Hills who oppose putting turbines there don't speak to him anymore. "It's sad what he's doing," says Susan Barnes, owner of the Grand Central Hotel in Cottonwood Falls. "I'm sure wind helped save his ranch, but there are other ways."

Kansas Governor Sibelius has emerged as a

vocal proponent of wind energy

Chuck France /AP Photo

The era of the small-time wind developer may already be passing, anyway. Ferrell says it's tough to compete with big outfits with economies of scale and easier access to capital. It costs roughly $225 million to build a 150-megawatt wind plant. Horizon, the big wind developer, has 11,000 megawatts of projects in the works and is hoping to add Ness County to the list. A few days after the meeting in Bazine, Ferrell calls Antenen to say he won't bid on the project. There's a shortage of good transmission lines in the area, and it could take several years to upgrade them.

Even the big players need government help to get major wind projects off the ground. Twenty-five states require their utilities to use a percentage of renewable energy, and in all of them, alternative-energy projects rely on the federal government's production tax credit. That expires at the end of this year, so wind advocates are pressing Congress to renew it. In the past, every time it was allowed to expire, wind development plummeted the following year.

It's morning at the Ferrell Ranch. In the house the family built in 1923, Ferrell's mother, 95-year-old Isabelle, sits in the living room while Pete helps her put on support stockings. A tiny woman with a shock of white hair, she says she likes to look at the wind turbines outlined against the blue sky. Her favorite memories, she says, are of riding the range on horseback in the old days with her late husband, Jack. "He'd say we're just stewards of the land," she says. "It's Pete's feeling and mine. You've got to take care of the land."

Hamm is a senior writer for BusinessWeek in New York.

http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/08_27/b4091046392398.htm