Undersea volcanic rocks offer vast repository for GHGs

Public Release

Earth Institute at Columbia University

14-Jul-2008

Drilling, experiments, target huge formations off West Coast

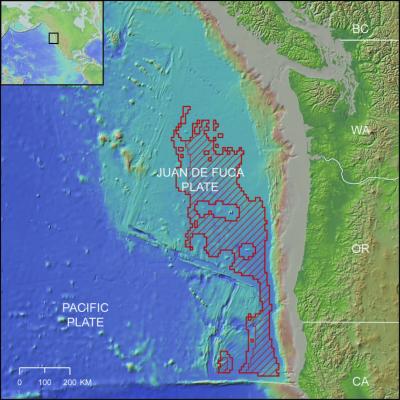

Deep-sea basalt region for CO2 burial. Red outline shows where water depth

exceeds 2,700 meters and sediment thickness exceeds 200 meters; hatched

areas show where sediment thickness exceeds 300 meters....

Palisades, N.Y., July 14, 2008—A group of scientists has used deep ocean-floor drilling and experiments to show that volcanic rocks off the West Coast and elsewhere might be used to securely imprison huge amounts of globe-warming carbon dioxide captured from power plants or other sources. In particular, they say that natural chemical reactions under 78,000 square kilometers (30,000 square miles) of ocean floor off California, Oregon, Washington and British Columbia could lock in as much as 150 years of U.S. CO2 production. The findings are published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Interest in so-called carbon sequestration is growing worldwide. However, no large-scale projects are yet off the ground, and other geological settings could be problematic. For instance, the petroleum industry has been pumping CO2 into voids left by old oil wells on a small scale, but some fear that these might eventually leak, putting gas back into the air and possibly endangering people nearby.

Basalts on seafloor near Juan de Fuca Ridge. Image shows about 3 by 4.5 feet.

Lead author David Goldberg, a geophysicist at Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, called the study "the first good evidence that this kind of carbon burial is feasible."

"We are convinced that the sub-ocean floor is a significant part of the solution to the global climate problem," said Goldberg. "Basalt reservoirs are understudied. They are immense, accessible and well sealed--a huge prize in the search for viable options." One of the main advantages, he said, is a chemical process between basalt and pumped-in CO2 that would convert the carbon into a solid mineral.

In their paper, Goldberg and his colleagues Taro Takahashi and Angela Slagle used previous deep-ocean drilling studies of the Juan de Fuca plate, some 100 miles off the Pacific coast, to chart a vast basalt formation that they say could be suitable for such pumping. Basalt, the basic stuff of the ocean floors, is hardened lava erupted from undersea fissures and volcanoes. In this region, much of it lies under some 2,700 meters (8,850 feet) of water, and 200 meters (650 feet) or more of overlying fine-grained sediment. Drilling by the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program has shown the rock is honeycombed with watery channels and pores that would provide room for pressurized CO2. The scientists have mapped out specific areas that they say are isolated from earthquakes, hydrothermal vents or other factors that might upset the system.

Ongoing experiments by Lamont scientists on land have shown that when CO2 is combined with basalt, the gas and components of the rock naturally react to create a solid carbonate—basically, chalk. Later this year, a separate team headed by Lamont geochemist Juerg Matter will begin pumping CO2 into a landbound basalt formation at a power plant near Reykjavik, Iceland—the first such large-scale demonstration. Basalts lie at or near the surfaces of other land areas including the northeast United States; the Caribbean; north and south Africa; and southeast Asia.

Goldberg says that undersea basalts, which are widespread, may be bigger, and better, than ones on land. At the depths studied, any CO2 that does not react with the rock will be heavier than seawater, and thus unable to rise. And in places like the Juan de Fuca, even if some did escape the rock, it would hit the overlying impermeable cap of clayey sediment.

Skeptics point out that getting the CO2 to such sites could be expensive and tricky. But Goldberg says the West Coast formations should be close enough to the land for delivery by pipelines or tankers. He called on government to study the details of how the idea might work, and whether it would be economically feasible. The United States currently spends about $40 million a year studying carbon sequestration, but nearly all of that goes to land-based research. "Forty million is about the opening-day box office for Finding Nemo," said Goldberg. We need policy change now, to energize research beyond our coastlines."

###

Art or advance copies of the paper, "Carbon dioxide sequestration in deep-sea basalt," are available from the authors, PNAS, or The Earth Institute. It is now downloadable as an Earth Institute Open Access Article, from here.

Authors: David Goldberg (lead) Goldberg@ldeo.columbia.edu 845-365-8674

Taro Takahashi taka@ldeo.columbia.edu 845-365-8537

Angela Slagle aslagle@ldeo.colubmia.edu 845-365-8339

Earth Institute press office: Kevin Krajick kkrajick@ei.columbia.edu

212-854-9729 Mobile: 917-361-7766

PNAS press office: pnasnews@nas.edu 202-334-1310

The Earth Institute at Columbia University mobilizes the sciences, education and public policy to achieve a sustainable earth. Through interdisciplinary research among more than 500 scientists in diverse fields, it is adding to the knowledge necessary for addressing the challenges of the 21st century and beyond. With over two dozen associated degree curricula and a vibrant fellowship program, the Earth Institute is educating new leaders to become professionals and scholars in the growing field of sustainable development. We work alongside governments, businesses, nonprofit organizations and individuals to devise innovative strategies to protect the future of our planet. Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, a member of The Earth Institute, is one of the world's leading research centers seeking fundamental knowledge about the origin, evolution and future of the natural world. More than 300 research scientists study the planet from its deepest interior to the outer reaches of its atmosphere, on every continent and in every ocean. From global climate change to earthquakes, volcanoes, nonrenewable resources, environmental hazards and beyond, Observatory scientists provide a rational basis for the difficult choices facing humankind in the planet's stewardship.

http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2008-07/teia-uvr071108.php

Scientists tout Pacific floor for massive carbon capture project

Margaret Munro

Canwest News Service

Monday, July 14, 2008

Vast amounts of greenhouse gases could be stashed under the ocean floor from British Columbia to California say scientists, who have ambitious plans to start testing deep-sea disposal.

The geological formations off the Pacific Northwest coast "offer promising locations to securely accommodate more than a century of future U.S. emissions," the team, led by geophysicist David Goldberg at Columbia University, reported Monday in the U.S. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. [Download report here]

The researchers hope to begin a pilot project as early as next year injecting liquefied carbon dioxide below the ocean floor, Goldberg said in an interview. He says the project, which would cost about $50 million, still needs to be approved by U.S. National Science Foundation and the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program.

A handout graphic shows the location of undersea

volcanic rocks which scientists say could be used

as a vast repository for greenhouse gases.

They would pump the CO2 into test wells on the Juan De Fuca Plate, an enormous basalt formation that runs from Vancouver Island to California about 150 kilometres off shore. The researchers say the plate, made of hardened lava, is honeycombed with watery channels and pores that could hold plenty of pressurized CO2.

While the region is famous for earthquakes and seismic activity, Goldberg and his colleagues have mapped out a 68,000-square-kilometre area they say would be isolated from quakes, hydro thermal vents or other factors that might upset a CO2 storage system. The region is in international waters, just south of B.C. and off the coast of Washington, Oregon and California.

"It is very large and very secure," says Goldberg, noting that "big solutions" are needed for the planet's greenhouse gas emission problems.

The proposed disposal area is in under more than two kilometres of seawater and more than 200 metres of clayey sea floor sediments. Both the water and the sediments would help keep the CO2 in place even in the event of a massive quake, says Goldberg.

Deep ocean drilling experiments have revealed spots around the globe, that might be used to "securely imprison" carbon dioxide captured from power plants or other sources. The potential storage capacity is huge, say Goldberg and his colleagues, who estimate that Juan de Fuca formation "could lock in as much as 150 years of U.S. CO2 production."

The big attraction is that over time the CO2 would become locked into the rock. This is because CO2 and basalt naturally react to create a solid carbonate, which Goldberg says is "basically chalk."

Part of the pilot project would be to assess how long it would take CO2 to react with the rocks - a process that might take anywhere from "decades to a century," he says.

There is plenty of talk about carbon capture and sequestration, but no large-scale projects are yet off the ground because of the cost, technical challenges, and environmental concerns.

Goldberg says the deep-ocean disposal has some clear advantages over plans, popular in Canada, to pump CO2 into old oil wells. There is concern that the CO2 might eventually leak out and drift into the atmosphere.

Goldberg says while ocean disposal would be more expensive, the advantage is that the carbon would eventually be locked up as a solid compound.

While "convinced" sub-ocean disposal can be a significant part of climate change solution, Goldberg says it will take several years to evaluate the feasibility. The proposed pilot would entail pumping a few thousands tonnes of liquefied CO2 into wells that have been previously drilled in the Juan de Fuca plate. Then the researchers would monitor the CO2 and how quickly it reacts with the basalt.

Goldberg team says the West Coast formations should be close enough to the land for delivery by pipelines or tankers.

© Canwest News Service 2008

Posted by Arthur Caldicott on 16 Jul 2008