Bye, Bubble? The Price of Oil May Be Peaking

Andrew Bary

Barron's

June 23, 2008

IT'S PERILOUS TO CALL THE TOP IN A BOOMING MARKET, but the price of oil may be peaking in the current range of $130 to $140 a barrel.

Oil's sharp move up -- prices have doubled in the past year -- caught the world by surprise, including almost everyone involved in the petroleum market, from major exporting nations to big energy companies to the global analyst community. The rally has emboldened oil bulls, who argue the world is bumping up against oil-supply constraints, and that demand will rise inexorably, despite sharply higher prices, as the four billion to five billion people in emerging economies like China and India get a taste of the energy-intensive good life, replete with the cars, air conditioners, refrigerators and computers that Americans and Western Europeans have long enjoyed. Statistics support their view that demand growth is in its infancy in the developing world: U.S. per-capita oil consumption is 25 barrels annually, while Japan uses 14 barrels per person. China's 1.3 billion people consume just two barrels each per year, however, and India's 1.1 billion use less than a barrel a year.

In the next decade, oil indeed may hit $200 a barrel. But prices could fall to $100 a barrel by the end of this year if Saudi Arabia makes good on its pledge to increase production; global demand eases; the Federal Reserve begins lifting short-term interest rates; the dollar rallies, and investors stop pouring money into the oil market. China raised prices on retail gasoline and diesel fuel by 18% Thursday, in a move that is expected to curb demand.

It's tough to know how much of the surge in crude-oil prices -- up 40% just this year -- reflects fundamental supply and demand, and how much is due to other factors, including the dollar, commodity speculation and interest from institutional investors. Like some others, we suspect the run-up was fueled by more than economics.

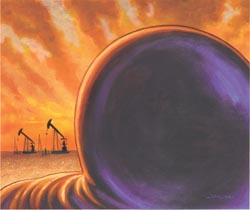

Jason Edmiston

THERE IS GROWING TALK OF AN OIL BUBBLE, THOUGH evidence of asset bubbles isn't conclusive until they burst. The trajectory of oil prices in the past eight years looks eerily similar to the Nasdaq's eight-year run to a peak of more than 5,000 in March 2000. More than eight years later, the Nasdaq is at half that level.

"My basic message to those who say that prices have to go up forever is that the oil markets have been cyclical for 140 years. Why should that have stopped?" says Edward Morse, chief energy economist at Lehman Brothers.

Saudi Arabia, the world's biggest oil exporter, has pledged to boost production from a recent 9.5 million barrels a day to about 9.7 million in order to reduce prices. The Saudis are hosting a summit of oil producers and consumers on June 22.

"The analytic community is divided on what the recent Saudi comments mean for the market," says Morse, who believes the Saudis will put more oil on the market as they raise production. "That, combined with a declining rate of consumption, should create an inventory surplus that will be palpable as the year progresses."

Morse thinks oil could fall to $100 by year end.

Skeptics say the Saudi vow to boost production is merely talk, and that the country is struggling simply to maintain production because of aging, overworked fields like the huge, 60-year-old Ghawar reservoir. The Saudi government refuses to allow in outsiders to evaluate the state of its oil industry, which has fueled talk the Saudis are hiding something.

Likewise, the size of speculative positions and commodity indexers is impossible to determine, as most trading occurs away from the major commodity exchanges in over-the-counter transactions.

It is hard to argue that oil demand supports $135 crude. Now at 86 million barrels a day, global demand could show little or no increase this year after averaging 1% gains in recent years. Sanford Bernstein analyst Neil McMahon projects that by the fourth quarter, global oil demand could be running below the fourth quarter of 2007.

Consumption is down in '08 in the 30 member nations of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which includes the U.S., Western Europe, Japan and Australia. OECD nations account for 57% of global oil demand.

While Americans are married to their cars, $4-a-gallon gasoline has begun to bite; the number of vehicle miles traveled in the U.S fell in March on a year-over-year basis for the first time since 1979. Further declines in gasoline consumption may follow as drivers opt for more fuel-efficient cars, and as innovations like plug-in cars reach the market after 2010. Major U.S. airlines have announced widespread capacity reductions, which could cut demand for jet fuel by 5% or more later this year.

Oil demand continues to grow in the developing world and the Middle East. In Europe, stiff energy taxes generally blunt the impact of higher prices, but diesel fuel, now at nearly $10 a gallon in Britain (double the American price), may be at an unsupportable level. Demand growth could cool in emerging markets, too, as subsidies in many Asian countries are reduced. There is also speculation China has been hoarding diesel fuel ahead of the Olympics in August, in order to cut the use of coal for power generation around Beijing in the hope of cleaning up the city's notoriously polluted air. Once the games are over, China will go back to burning cheaper coal, the story goes.

The supply/demand argument for higher oil prices has some merit. "Name another commodity that has gone up two-and-a-half times in three-and-a-half years and the world hasn't found a way to make more of it," says Byron Wien, chief investment strategist at Pequot Capital Management. "The world isn't finding oil fast enough to replace the 3% to 4% that gets pumped every year."

Wien's boss, Art Samberg, who heads the Westport, Conn.-based investment firm, stated in Barron's midyear Roundtable, published last week, that the commodity bubble "isn't going to burst. It's going to continue to expand." Older oil fields in Mexico and the North Sea are running dry while new sources in places like Kazakhstan and Brazil may prove difficult to bring on stream. In addition, oil increasingly is in the hands of government-run monopolies that may be more interested in maximizing future revenue than boosting current production.

Attachment: An Oil Overview

The dollar's slide and the Federal Reserve's neglect of the greenback have supported commodity prices, oil in particular. But Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke and his colleagues finally seem to have realized that the Fed's aggressive easing actions since last summer, which dropped the key federal-funds rate to 2% from 5.25%, may be fueling global inflation. If the Fed moves to lift rates later this year, as financial markets anticipate, it could buttress the dollar and spur an exodus of speculators from the oil market.

One little-discussed way the U.S. could try to bring down oil prices is to sell oil from the strategic petroleum reserve (SPR). The SPR, intended as a source of oil for national emergencies, now holds 705 million barrels of crude, equal to about 35 days of domestic consumption. With prices higher, Congress moved in May to stop adding to the SPR as it neared capacity. A sale of 100 million barrels of oil would shock the markets and potentially drive down prices.

Long term, the U.S. could benefit through lower oil prices if Congress and the states back President Bush's proposal to allow drilling off Florida, the East and West coasts, and in the Alaskan National Wildlife Reserve, where billions of barrels of oil may lie.

A SHARP DROP IN ENERGY PRICES WOULD HELP WHOLE swaths of the U.S. economy, including retailers, food and household-goods makers, auto makers and transportation concerns. Beleaguered U.S. airlines would benefit because they're expected to spend $61 billion on fuel this year, up $20 billion from 2007.

Few oil stocks would be safe if crude falls $20 to $30 a barrel. Independent exploration and production companies like Devon Energy (DVN), Apache (APA) and XTO Energy (XTO) could get hit hard because they're up sharply in the past year. The majors, including ExxonMobil (XOM), Chevron (CVX) and ConocoPhillips (COP), might hold up better because they have refining and related businesses like chemicals, whose profitability isn't directly linked to crude and natural-gas prices.

Some of the biggest oil companies, notably ExxonMobil, Royal Dutch Shell (RDS/A) and BP (BP), have badly lagged in the past year. BP, for one, has been beset by problems, including a troubled joint venture in Russia.

The majors may be the best energy values because they trade for less than 10 times this year's earnings and around eight times estimated 2009 profits. The '09 earnings consensus reflects an assumption of $100 crude, not the current $135. Bernstein's McMahon estimates Exxon could earn $12 share in 2009, versus the current consensus of $9, if oil holds $130 and natural gas averages $11 per thousand cubic feet; it is now around $13. This suggests Exxon, at 86, may be trading for just seven times estimated '09 profits. Conoco and Chevron also could earn far more than the current '09 consensus under the same oil and gas scenario, Bernstein estimates. McMahon favors BP, Royal Dutch and Marathon Oil (MRO).

One reason for the strength in crude has been modest U.S. inventories. Bill Klesse, chief executive of Valero Energy (VLO), the largest North American oil refiner, told analysts last month that the inventory data may be misinterpreted as a sign of oil scarcity, though it is more a function of the recent state of the oil market, in which futures prices were below spot prices, giving refiners little incentive to maintain excess supply. If the Saudis sell enough oil to drive down spot prices relative to futures prices, refiners and others will be induced to buy and hold more oil in inventory, he said. The oil market is moving to such a configuration, with the current, or spot price of $135 below the December 2008 price of $136.

OIL-MARKET EXPERTS ACKNOWLEDGE THAT commodity-indexing strategies employed by endowments, pension funds and other institutional investors have helped push up prices in the past year. Such investments are thought to have totaled $260 billion as of March, up from $13 billion at the end of 2003, according to Michael Masters, the head of Masters Capital Management, an Atlanta investment firm. Some $55 billion may have flowed into commodity investments during the first quarter alone. The energy complex is the largest commodity market, and gets a disproportionate share of fund flows. Masters estimates index participants may control over 1 billion barrels of crude.

Managers of leading university endowments, including those at Harvard, Yale and Princeton, in recent years have generated outsized returns from investments in hard assets, prompting other investors, such as the giant California Public Employees Retirement System, with over $200 billion in assets, to attempt the same. Calpers is upping its commodity exposure to $7 billion from under $500 million.

This activity is spurring a backlash in Congress, where pension funds and others have been accused of driving up food and energy costs through their increased commodity investments. Lawmakers including Senator Joe Lieberman (independent, Conn.) have proposed a ban on commodity-related investments by pension funds, which Masters supports. Last month he told Congress that commodity regulators need to close a loophole that lets indexers evade commodity-position limits by purchasing over-the-counter swaps and other derivatives.

A selloff in oil and other commodities could cool the ardor for index strategies. Ross Margolies, head of Stelliam Investment Management, in New York, says financial investors would do better buying the shares of commodities producers, not actual goods. Over time, it may be more difficult to make money in commodity investing because holders effectively incur financial costs to carry and store commodities, even if they never take physical delivery.

Though little noticed, short-covering by independent oil and gas producers might have contributed to the recent strength in oil and gas prices. U.S. exploration and production companies like Devon, XTO and Chesapeake Energy (CHK) have hedged an average of about 40% of their 2008 production by selling oil and gas futures, options or derivatives, according to Credit Suisse analyst Jonathan Wolff. As prices have surged, the hedges have slipped underwater, and some producers have sought to unwind their money-losing bets.

Newfield Exploration (NFX) recently announced a $500 million hedge-related loss, and more red ink could follow. Total hedge losses among E&P companies could top $15 billion for 2008, and $8 billion for 2009, Wolff estimates.

While supply challenges could continue to dog the oil market, current prices seem excessive in light of weakening demand and other factors. But it's impossible to know with precision when the bubble will burst. The Saudis could roil the markets with a pronouncement June 22; the dollar could revive or demand could plummet, or all three. And if prices start falling, the downturn could accelerate, sending crude back to $100 -- where it would be cheaper, but still far from cheap.

E-mail comments to mail@barrons.com