The great coal hole

By David Strahan

New Scientist

17 January 2008

There used to be a joke about taking coal to Newcastle but these days the laughing stock is getting the stuff out. Newcastle in New South Wales, Australia, may be the biggest coal export terminal in the world’s biggest coal-exporting country, but even it is having trouble keeping up with demand. The line of ships waiting to load coal can stretch almost to Sydney, 150 kilometres to the south. At its peak last year, there were 80 vessels in the queue, each forced to lie idle for up to a month.

The delays have been lengthening since 2003 – and not just because of the port’s limited capacity in the face of soaring demand. Gnawing doubts are also beginning to emerge about supply, not just in Australia but worldwide, and not only because of logistics but also because of geology. In other words, coal may soon be running short.

Ask most energy analysts how much coal we have left, and the answer will be a variant on “plenty”. It is commonly agreed that supplies of coal will last for well over a century; coal is generally seen as our safety net in a world of dwindling oil. But is it? A number of recent reports suggest that coal reserves may be hugely inflated, a possibility that has profound implications for both global energy supply and climate change.

The latest “official” statistics from the World Energy Council, published in 2007, put global coal reserves at a staggering 847 billion tonnes. Since world coal production that year was just under 6 billion tonnes, the reserves appear at first glance to be ample to sustain output for at least a century – well beyond even the most distant planning horizon.

Mine below the surface, however, and the numbers are not so reassuring. Over the past 20 years, official reserves have fallen by more than 170 billion tonnes, even though we have consumed nothing like that much. What’s more, by a measure known as the reserves-to-production (R/P) ratio – the number of years the reserves would last at the current rate of consumption – coal has declined even more dramatically. In February 2007, the European Commission’s Institute for Energy reported that the R/P ratio had dropped by more than a third between 2000 and 2005, from 277 years to just 155. If this rate of decline were to continue, the institute warns, “the world could run out of economically recoverable …reserves of coal much earlier than widely anticipated”. In 2006, according to figures from the BP Statistical Review of World Energy, the R/P fell again, to 144 years. So why are estimates of coal reserves falling so fast – and why now?

One reason is clear: consumption is soaring, particularly in the developing world. Global coal consumption rose 35 per cent between 2000 and 2006. In 2006, China alone added 102 gigawatts of coal-fired generating capacity, enough to produce three times as much electricity as California consumed that year. China is by far the world’s largest producer of coal, but such is its appetite for the fuel that in 2007 it became a net importer. According to the International Energy Agency, coal consumption is likely to grow ever faster in both China and India.

Another less noticed reason is that in recent years many countries have revised their official coal reserves downwards, in some cases massively, and often by far more than had been mined since the previous assessment. For instance, the UK and Germany have cut their reserves by more than 90 per cent and Poland by 50 per cent. Declared global reserves of high-quality “hard coal” have fallen by 25 per cent since 1990, from almost 640 billion tonnes to less than 480 billion – again more than could be accounted for by consumption.

At the same time, however, many countries including China and Vietnam have left their official reserves suspiciously unchanged for decades even though they have mined billions of tonnes of coal over that period.

Taken together, dramatic falls in some countries’ reserves coupled with the stubborn refusal of others to revise their figures down in the face of massive production suggest that figures for global coal reserves figures are not to be relied on. Is it possible that the sturdy pit prop of unlimited coal is actually a flimsy stick?

That is certainly the conclusion of Energy Watch, a group of scientists led by the German renewable energy consultancy Ludwig Bölkow Systemtechnik (LBST). In a report published in 2007, the group argues that official coal reserves are likely to be biased on the high side. “As scientists we were surprised to find that so-called proven reserves were anything but proven,” says lead author Werner Zittel. “It is a clear sign that something is seriously wrong.”

Since it is widely accepted that major new discoveries of coal are unlikely, Energy Watch forecast that global coal output will peak as early as 2025 and then fall into terminal decline. That’s a lot earlier than is generally assumed by policy-makers, who look to the much higher forecasts of the International Energy Agency, which are based on official reserves. “The perception that coal is the fossil resource of last resort that you can come back to when you run into problems with all the others is probably an illusion,” says Jörg Schindler of LBST.

![]()

According to the Energy Watch analysis, world coal production will peak in around 2025. In that case output would undershoot official forecasts from the International Energy Agency’s World Energy Outlook (WEO) by a substantial margin. Source: Energy Watch Group

A look at how official global reserves are calculated does little to bolster confidence. The figures, compiled by a husband-and-wife energy consultancy called Energy Data Associates based in Dorset, UK, are gathered principally by sending out a questionnaire to the governments of 100 coal-producing countries. Officials are asked to supply figures under clearly defined guidelines, but many do not. “About two-thirds of the countries reply,” says Alan Clarke of Energy Data Associates, “And maybe 50 are usable.”

Top ten holders of proved recoverable reserves. Source: World Energy Council Survey of Energy Resources 2007

Some countries have been known to make elementary errors filling in the forms, often with the effect of massively increasing their reserves. Undoing these apparently innocent mistakes has led to some of the major downward revisions of recent years.

Although Clarke defends his data as the best available, he is also the first to admit that there are shortcomings. “It’s no secret that the result is a bit of a ragbag. It ranges from well-established estimates for some countries to others that are fairly airy-fairy, and some that are highly political and not to be believed.”

Figures for two of the world’s biggest coal producers are particularly hard to glean. Russia has failed to update its numbers since 1996, China since 1990. “There is really nothing very certain or clear-cut about reserves figures anywhere,” Clarke says. Even senior officials in the coal industry admit that the figures are unreliable. “We don’t have good reserves numbers in the coal business,” says David Brewer of CoalPro, the UK mine owners’ association.

Annual production in the top ten coal producers. Source: World Energy Council Survey of Energy Resources 2007

Even so, the industry consensus rejects thoughts of an imminent shortage, or “peak coal. Milton Catelin of the World Coal Institute, the international producers’ trade body, admits that he does not understand what has led to the reductions in quoted figures for reserves, but insists that it is not down to a lack of coal. “With regard to coal the world is not resource limited,” he says. “It’s limited only by the economics of recovery and environmental concerns.”

The industry position is born of the traditional view that “reserves” is essentially an economic concept – the amount of coal that could be produced at today’s prices using existing technology. This is not the same as “resources” – the total amount of coal that exists. Seen in this light reserves are, to some extent, replenishable. If shortage bites and prices rise, uneconomic resources – seams that are too thin, too deep or too remote from markets – become economic and can be reclassified as reserves. And because global resources are vastly greater than global reserves, the industry argues there can be no imminent shortage. “It’s there if the price is high enough,” Brewer says. “It’s all a matter of price.”

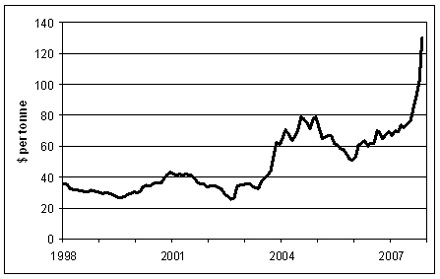

Northwest Europe Steam Coal Marker Price. Source: McCloskey Group

Problem is, the real world seems to have forgotten this piece of economic lore. Although the price of coal has quintupled since 2002, reserves have still fallen. This is similar to what is happening with oil, where fresh reserves have not been forthcoming despite soaring prices. To a growing number of oil industry commentators this is because we have reached, or are just about to reach, peak oil – the point at which oil production hits an all time high then goes into terminal decline.

Some experts are starting to reach a similar conclusion about coal. “Normally when prices go up, mine managers ramp up production as fast as possible and shortage quickly turns to glut,” says coal geologist Graham Chapman of the consultancy Energy Edge in Richmond, Surrey, UK. “This time it hasn’t happened.”

He concludes that the industry has already produced most of the easily mined coal and “from now on it’s going to be a significant challenge”. In China, for example, much of the remaining coal is more than 1000 metres below the surface, Chapman says, while in South Africa the geology is extremely complex. Elsewhere, flooding and subsidence may have “sterilised” significant reserves: the coal is there, but will almost certainly never be mined. As a result, Chapman agrees that true reserves are probably much lower than the official figure.

David Rutledge, chair of Engineering and Applied Science at the California Institute of Technology, shares this view. He became interested in coal after attending a presentation on climate change at which the levels of carbon emissions from fossil fuels were thought too uncertain to be specified. Although the issue was not strictly on his patch, Caltech has a healthy interdisciplinary tradition and early in 2007 Rutledge decided to have a go at solving the uncertainty. The results are even more dramatic than those of Energy Watch.

To forecast coal production Rutledge borrowed a statistical technique developed for oil forecasting known as Hubbert linearisation. M. King Hubbert, after whom the method is named, was a the Shell geologist who founded the peak oil school of thought. In 1956 Hubbert famously predicted that US oil production would peak within 15 years and go into terminal decline. He was vindicated in 1970.

Although accurate, Hubbert’s original forecast depended on the idea that oil peaks when half has been consumed, and half is still underground. So the date of the peak can only be predicted if you have a reasonably accurate estimate of the total oil that will ever be produced. Such estimates can be unreliable – and are worse in the case of coal. Hubbert linearisation, published in 1982, solves this problem by presenting the numbers in a different way.

Linearisation works by plotting annual production as a percentage of total production up to that point (on the vertical axis), against total production on the horizontal axis. This produces a graph showing how the percentage growth rate of total production changes as the resource is extracted (see graphs below). For oil, this percentage generally declines from almost the earliest days of production, even when annual output is still rising, and soon settles into a roughly straight downward-sloping line. By extending the line to the bottom of the graph, you can deduce the total amount that will ever be produced. “Once you have a straight line,” says Rutledge, “you’re off to the races.”

Top: UK coal production since 1855. Bottom: Hubbert linearization of UK coal production since 1855. Source: Prof Dave Rutledge, Caltech

To test the linearisation technique for coal, Rutledge applied it to historical data for UK production, which peaked in 1913. He says it provides a better model of the decline since then than traditional economics, which tends to blame factors such as foreign competition and Winston Churchill’s decision to switch the navy to oil, and later the displacement of coal by natural gas. Because the straight-line decline in the growth rate of total production starts long before the peak and continues long after, for Rutledge this suggests the cause is fundamentally geological, reflecting the increasing difficulty of expanding production while exploiting resources of progressively poorer quality. “Had you known this method in the 1920s,” Rutledge says, “you could have predicted accurately where British coal output is today.”

He has also applied it to today’s major coal-producing countries, including the US, China, Russia, India, Australia and South Africa – with startling results. Hubbert linearisation suggests that future coal production will amount to around 450 billion tonnes – little more than half the current official reserves.

The idea of an imminent coal peak is very new and has so far made little impact on mainstream coal geology or economics, and it could be wrong. Most academics and officials reject the idea out of hand. Yet in doing so they tend to fall back on the traditional argument that higher coal prices will transform resources into reserves – something that is clearly not happening this time.

So what if coal does peak much sooner than most people expect? According to the International Energy Agency’s latest long-term forecast, economic growth will require global coal production to rise by more than 70 per cent by 2030, so if Rutledge is right, the world is heading for an energy crisis even worse than many already predict. Hopes that coal-derived liquid fuels will be able to step in as oil runs out will also be dashed.

The sliver lining to this gloomy scenario is its effect on climate. Forecasts by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change assume more or less infinite replenishment of coal reserves, in line with traditional economic theory. Less coal means less carbon dioxide, so the impact on emissions could be enormous. Using one of the IPCC’s simpler climate models, Rutledge forecasts that total CO2 emissions from fossil fuel will be lower than any of the IPCC scenarios. He found that atmospheric concentration of CO2 will peak in 2070 at 460 parts per million, fractionally above what many scientists believe is the threshold for runaway climate change. “In some sense this is good news,” Rutledge says. “Production limits mean we are likely to hit the general target without any policy intervention.”

C02 emissions and peak concentration are lower Rutledge’s producer-limited profile than all 40 IPCC SRES scenarios. Source: Professor Dave Rutledge, Caltech

Neither Energy Watch nor Rutledge could remotely be described as climate-change deniers – quite the opposite – but their findings worry many climate scientists, including Pushker Kharecha at the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York. He agrees that coal reserves are probably overstated, but insists that curtailment of coal emissions is still essential to combat climate change. He gives a simple reason for this view: “What are the risks if the low-coal people are wrong?” To pin our hopes on low coal would be dangerously complacent, he argues, because if it is only marginally wrong the additional emissions could ensure catastrophe.

Whoever turns out right, the good news is that the imperatives of climate change and peak coal are identical. “In the long run, economies that rely on depletable resources are doomed to fail,” says Zittel. “The coal peak makes it even more urgent to switch to renewable energy without delay.”

Posted by Arthur Caldicott on 17 Jan 2008