Russia’s Big Energy Secret

Putin wields gas as a weapon. But the reality is that Russia can barely meet its own growing demand.

By Owen Matthews

NEWSWEEK

Dec 22, 2007

Not Enough in the Pipeline: An oil and gas plant in Novy Urengoy, Russia. EPA-Corbis

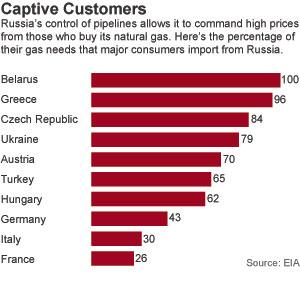

Gazprom, the Russian natural-gas giant, is often portrayed as the 1,000-pound gorilla of the energy world. Over the past few years, the company has had huge success in locking in lucrative European markets. It has also been ruthless about making consumers in the former Soviet Union pay something close to world prices for their gas—cutting off supplies, if necessary, to force reluctant customers like Ukraine to pay up. But problems are brewing. Gazprom, it turns out, has too many customers, and too little gas.

The surprising Achilles' heel of Gazprom is that it produces only about 550 billion cubic meters (bcm) of gas—just enough to supply its own domestic market. It relies on cheap imports from Central Asia to meet the majority of its other commitments to customers in Europe, amounting to nearly 80bcm. And since only Gazprom's foreign customers pay full market value, it's the company's exports which make up the bulk of Gazprom's revenues—$21 billion for the second quarter of 2007 alone. Now those nations on which Gazprom's profits rely—including Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan—are beginning to cut their own deals with big new customers like China. The deals are in turn becoming an existential threat to Gazprom, one of Russia's most valuable strategic levers of power.

Russian control of a quarter of Europe's gas supplies is a key plank of its foreign policy and renewed national pride; supply of cheap electricity and heat to Russian homes is a touchstone of the Russian government's credibility. Central Asia is now undermining both those fundamentals—and could threaten Vladmir Putin's petro-politics.

Gazprom hasn't opened up a new gas field since 1991, and its existing fields are dwindling. A recent report by the Russian Industry and Energy Ministry warned that if the decline continued, Russia may be unable to service even its own domestic gas needs by 2010, and recommended doubling prices, a conservation move that has upset business and could also put a damper on economic growth.

Meanwhile, Gazprom chairman Dmitry Medvedev—also first deputy prime minister and Vladimir Putin's anointed successor for the next presidential elections in March 2008—has announced a radical plan to revive the company's domestic production, investing $420 billion in exploration and new gas-production facilities.

Relying on cheap imports to supply foreign customers is nothing new for Gazprom; for years the company's been buying gas from the Central Asians for knockdown prices. Until earlier this year, Gazprom was paying just $65 per 1,000 cubic meters to the Turkmens—then selling the same gas to customers in Western Europe who pay up to $250 (possibly only because of Russia's pipeline monopoly). Now ''Russia's monopoly is under attack," says Steve Levine, author of "The Oil and the Glory," a study of Central Asia's energy politics. ''Other neighbors are starting to build pipelines, and local producers are getting smarter, too."

No threat is more potent than that of China's move into Turkmenistan. Last year China's President Hu Jintao signed a deal with the late Turkmen leader Sapurmurat Niyazov to buy 30bcm of Turkmen gas each year for the next 30 years, and finance a giant new gas pipeline to China's Xinjiang province. That's in addition to a deal signed with Iran in March, which promises 14bcm a year of Turkmen gas to Tehran. At the same time, the Turkmens have also signed a deal with Russia for 50bcm a year until 2009. ''There's no doubt that Turkmenistan has promised to sell more gas than it can feasibly pump," says one top U.S. diplomat in the region not authorized to speak on the record. ''The question is, which customer will they choose?"

A lot rides on that choice: no less, in fact, than the future of Russia as an energy superpower. But Gazprom insists there's no problem. ''We do not consider China to be a threat or a competitor in Central Asia," says Gazprom spokesman Igor Volobuyev. ''We have a 25-year, long-term contract with the Turkmen government; they are obliged to fulfil their responsibilities. Our contract with the Turkmens is longer than any of our contracts with our European customers." Putin earlier this year assured Gazprom customers that ''there is complete certainty that Russia will fulfill all its contracts."

Europeans now fret about possible shortages, even as Americans are gleeful. It's no secret that the United States would like to put a dent in Russia's stranglehold over the region's energy resources—as well as shake Putin's ''complete certainty" a little. The diplomatic code word is "encouraging diversity of supply"; deciphered, that means encouraging any and every other pipeline project that bypasses Russia. ''It's one of those areas where we and Beijing see pretty much eye to eye," says the U.S. official in the region. ''The more export routes there are, the happier we'll be."

To that end, the United States is encouraging a number of pipeline projects that cut Russia out of the loop; only one has been built so far, connecting Baku, Azerbaijan, to the energy-rich Caspian direct to the Mediterranean—but the United States hopes that others will follow. Needless to say, Moscow is working hard to keep its monopoly from being undermined. It most recently signed a new deal with Kazakhstan this past September to build a pipeline on the Caspian coast to Russia.

For the Central Asians themselves, selling energy is more than a matter of dollars and cents; it's about winning real independence from an old colonial master. One Kazakh government minister—who didn't wish to have his name used while criticizing Russia—recalls a recent incident when a Russian ministry didn't bother to send a car to pick up visiting Kazakh officials in Moscow. "Kazakhstan is constantly being treated like a kid brother by our Russian neighbors," he complains. Another slight was the banning of all Lufthansa planes from Russian airspace last month after the German company prepared to switch its Asian cargo hub from Krasnoyarsk in Russia to Astana in Kazakhstan. "The Russian government thought they would frighten us by flexing their muscles, the same way they did with Georgia and Ukraine," says the minister. "But we have others we can turn to."

It looks like China, rather than the United States, is best positioned to be the big winner in Central Asia's search for new friends. Though Washington has gone out of its way to turn a blind eye to the region's undemocratic practices, local despots are still irritated by even low-key criticism from the U.S. American insistence that the Central Asians forgo business with Iran also rankles. Kyrgyzstan, America's closest ally in the region, has been racked by instability and economic underperformance.

Kazakhstan, meanwhile, is booming, and plans to nearly double oil production to 150 million tons a year by 2015. A large chunk of that will be exported to China, through new Beijing-funded routes, or to other markets through the Baku-Ceyhan pipeline, bypassing Russia."Pretty soon the Chinese are going to exchange their bicycles for cars, so their oil needs will boom. We're happy to have such as a big, stable neighbor just on our border," says Kamal Burkhanov, a Kazakh parliamentarian. "How long should Central Asian countries be locked in by Gazprom's prices? The transit fees they pay us are kopecks."

True enough. For all its pretensions to being Europe's dominant energy supplier, Gazprom has stood on feet of clay. Now that Russia's former vassals are discovering their power, Moscow may have to ditch its trademark energy strong-arm tactics, and adopt a new gas diplomacy.

URL: http://www.newsweek.com/id/81557

See also Last Major Russian Field Goes Online

Posted by Arthur Caldicott on 25 Dec 2007