Role of major north slope producers unclear with signing of AGIA

COMMENT: Interesting comments about the waning popularity of the oil and gas industry in Alaska, corruption, Mackenzie Gas Pipeline, and nosing at the question as to how much subsidy and bribery it takes to get a major pipeline project built.

See also these somewhat related articles, Pipeline Canada and Stumping for VECO

There is more than you will ever want to read about the Alaska Gasline Inducement Act (AGIA) at Governor Sarah Palin's AGIA website (www.gov.state.ak.us/agia/)

AGIA is a set of inducements to companies to build a pipeline to move natural gas from Alaska's North Slope to "markets" - either LNG shipping to the continental US or through Canada to Alberta pipeline connections, with at least five delivery points in Alaska itself. The economic analysis used to build the AGIA is 4.5 billion cubic feet per day and a cost of US$20.5 billion (ahem). There are 35 trillion cubic feet of proven reserves in the North Slope and many more waiting to be discovered.

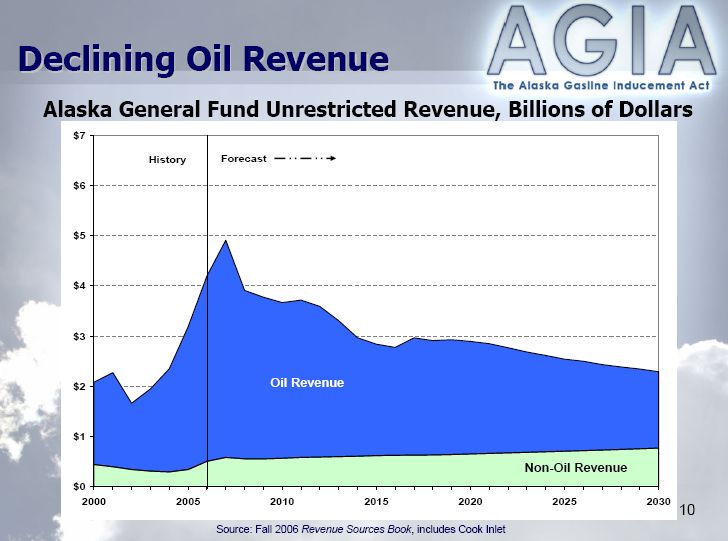

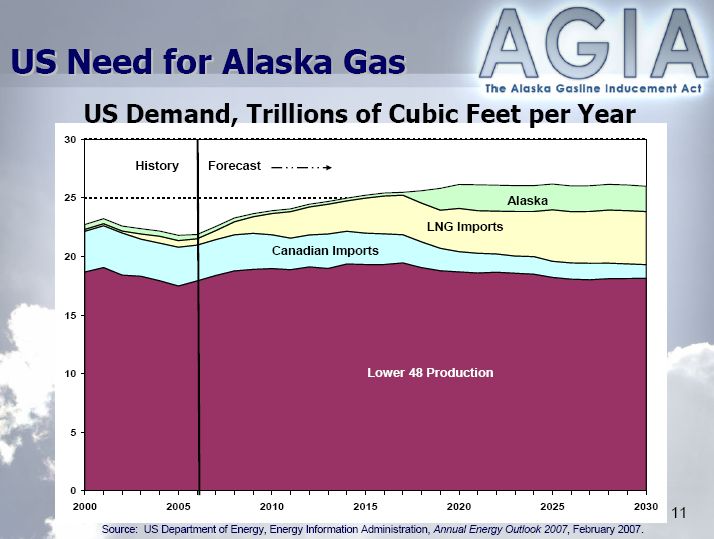

Here are a couple of charts showing Alaska's forecast decline in oil revenues and where the US expects to get its gas from in the next 23 years. 23 years - that's not a very long period of time, is it?

Role of major north slope producers unclear with signing of AGIA

Bill McAllister

KTUU Television

June 9, 2007

ANCHORAGE, Alaska -- The Alaska Gasline Inducement Act is now law. Gov. Sarah Palin signed the potentially historic legislation last night, setting up a competition to build the natural gas pipeline. But as Alaska moves into uncharted territory, the role of major north slope producers remains a big question mark.

The oil industry as a whole has fallen from the lofty perch it once enjoyed in public opinion polls in Alaska. One prominent public official says the recent corruption scandal involving oilfield services company VECO has tainted the producers as well. The producers have said they will not submit a bid under AGIA, but if they change their minds, they can expect to be under a strong spotlight.

"We cannot move the project forward if it is not commercially viable. AGIA, as written, does not provide for a commercially viable project," said Marty Massey, Exxon Mobil.

Before AGIA became law last night, all three of the major north slope producers testified before the Legislature that they would not compete for the rights to build the natural gas pipeline.

No one from BP, Exxon or Conoco Phillips would comment today, but one legislator says he expects them to change their minds.

"I'll be greatly surprised if they do not bid. They know this is an enormously profitable project. This is a project that will take their gas to market. I don't think they're going to stand on the sidelines and let someone else build that pipeline," said Sen. Hollis French, D-Senate Judiciary Chair.

But if the producers do compete, it will be in a climate in which they face new negative feelings and suspicions in the public.

Last month Ivan Moore Research found that public sentiment was barely in favor of the oil industry, with a positive rating of 44.8 percent compared to 43.1 percent negative. That's a drop from a positive of 53.3 percent in July 2005 and 76.4 percent in October 2001. Pollster Moore says that a slight recent drop in the numbers might be the result of the public corruption scandal involving guilty pleas by former executives of oilfield services company VECO.

"Clearly I think you've got the perception out there in the public that there's a degree of complicitness in the whole affair, which is driving down the popularity of the industry as a whole," said Ivan Moore.

A longtime critic of the industry, former legislator Jim Whitaker, who heads up the Alaska Gasline Port Authority, says the suspicion is warranted.

"If you've got a crooked politician, run his fanny down the road. Get rid of him. If they take money from the oil industry, it's tainted money. That money comes with a price tag associated with it. I've seen it. If you took money from the oil industry or from VECO or from contractors who work for the oil industry, it's clear, they expect you to respond to their requests for favorable legislation," said Whitaker.

But Sen. Hollis French, a former prosecutor, says there's no evidence to implicate the producers.

"It's a bit like blaming the Sierra Club for something that Greenpeace did. Obviously BP and Exxon and VECO have the same objectives and the same goals, but without some evidence, without an e-mail, without a document, without a wired phone call to show collusion, I think it's a stretch to say that BP and Exxon are responsible for what VECO did," said French.

The producers have no comment on any of that, either, and now Alaskans will have to wait for their next move.

During the ceremonial signing of AGIA on Wednesday, Fairbanks Rep. Jay Ramras noted the recent statement by the CEO of Exxon that neither the Mackenzie Pipeline in Canada nor the Alaska project is economic. Ramras says that indicates that Alaskans are in for a period of struggle with the producers.

Sen. French added his name to the list of politicians calling on Rep. Vic Kohring to resign.

Kohring himself put out a news release today saying he would announce his decision to the Wasilla Chamber of Commerce on June 19. In the news release Kohring acknowledged the increasing pressure for him to step down, but he said if he does so, it will not be an admission of guilt.

Contact Bill McAllister at

www.ktuu.com

A delicate balance between Slope's gas, oil

When Slope's gas is tapped, its oil must be protected, commissioner warns

By WESLEY LOY

Anchorage Daily News

Published: June 10, 2007

Over the Memorial Day weekend, Cathy Foerster and her husband flew to St. Paul Island, in the middle of the Bering Sea, and saw an abundance of Lapland longspurs, gray-crowned rosy-finches, rock sandpipers and even a great knot blown in from Asia.

"I confess -- Jane Hathaway and I are birders," said Foerster, a Texas-raised oil engineer and a fan of that old TV show "The Beverly Hillbillies."

Lately, Foerster has a bird of a different kind on her mind -- the North Slope oil reserves, or what she calls our "bird in the hand."

Her message is that Alaskans need to take great care not to kill that bird by rushing to produce our "bird in the bush" -- the natural gas that sits in the same fields as the oil.

Foerster, 52, a member of a state agency called the Alaska Oil and Gas Conservation Commission, has been on the speaking circuit lately, talking with considerable urgency to the Legislature, industry groups, even a local Lions Club.

Ignoring for a moment some complex technical details, her message is pretty simple: If we build a multibillion-dollar natural gas pipeline and start shipping gobs of gas, as many Alaskans have so long desired, we risk stranding millions upon millions of barrels of valuable crude oil deep underground. Forever.

And that could cost Alaska dearly.

The good news is Foerster and other experts see ways to avoid this costly tradeoff -- in short, a way to enjoy our bird in the hand and catch the bird in the bush too.

Foerster and her fellow members on the oil and gas commission -- lawyer John Norman and geologist Dan Seamount -- are key state decision-makers in planning for a gas pipeline to the Lower 48.

One of the agency's main jobs is to prevent waste -- that is, it aims to make sure every possible drop of oil and molecule of natural gas are wrenched from the rocks.

Two fields hold the bulk of the North Slope's estimated 35 trillion cubic feet of gas: Prudhoe Bay, the nation's largest oil field, with about 24 trillion cubic feet, and the undeveloped Point Thomson field to the east with perhaps 8 trillion.

At Prudhoe, gas plays a huge role in producing oil -- and that's why state regulators and the oil industry must think carefully before piping away the gas, Foerster said.

UNDER PRESSURE

The geologic structure that holds Prudhoe reserves is built kind of like a layer cake -- a layer of water on the bottom, a layer of oil next, topped by what is called the gas cap.

Over its nearly 30-year history, drillers have pierced those layers with some 2,600 holes. Production wells send a mixture of oil, gas and water to the surface, where they are separated.

Now here's the most important thing, the point Foerster wants you to hear: Most of that gas is shot back down into the ground, where it serves to keep pressure in the oil field and to keep the oil from migrating upward into "dry" rock, where it tends to stick like glue.

The pressurizing gas forces out more oil. It's like the aerosol in the can, Foerster said. The fizz in your soda pop.

To impatient Alaskans, Prudhoe's gas isn't going to market and thus isn't generating tax dollars and worker paychecks. But it's indirectly creating great wealth.

"That gas up there, it's doing all the heavy lifting to get the oil out," Foerster said.

STRANDING AN OIL FORTUNE

With Gov. Sarah Palin courting companies to build a gas line, the oil and gas commissioners are taking steps to determine how much natural gas can be siphoned off without significantly harming oil production.

Prudhoe, which is entering old age, still holds an oil fortune -- an estimated 2 billion barrels. The commission wants to make sure as much of that as possible is produced before significant gas is removed, Foerster said.

The agency recently hired an engineering consultant, Blaskovich Services Inc. of Aptos, Calif., to help study the impact of major gas sales on Prudhoe.

The commission in 1977 set a limit on how much gas producers could withdraw -- 2.7 billion cubic feet per day. The thinking then was that a gas pipeline would be built right away, and nobody expected Prudhoe would still be producing oil today, Foerster said.

Commissioners believe they might have to adjust this limit in light of the significant oil remaining in Prudhoe, the need for gas to help push it out, and the fact that builders want a pipeline capable of carrying as much as 4.3 billion cubic feet a day.

Commissioners have scheduled a June 19 hearing to discuss the consultant's report.

A decision on how much gas can leave Prudhoe is years away. First, the commissioners need to know when a gas pipeline will start operating, what volume of gas it will carry and how much oil is left in the field.

Gordon Pospisil, technology and resource manager for BP Exploration (Alaska) Inc., which runs the Prudhoe field, said he doesn't see a big oil sacrifice coming.

"We're very well-positioned to maximize oil recovery and produce the gas," he said.

AN ACE IN THE HOLE

One major recommendation from consultant Blaskovich is for oil companies to produce as much oil as possible from Prudhoe before a gas pipeline comes online. That's not expected for at least eight years.

The consultant also said it's important to avoid oil field breakdowns, such as last year's corrosion-related pipeline leaks, which can interrupt oil production.

The equation is simple: The more oil that's produced now, the less left stranded once major gas shipment begins.

Pospisil said his company has done many things to juice oil production now. These include drilling more wells to tap the oil, installing bigger compressors to force gas back underground, and flooding the field with billions of gallons of seawater to flush out oil.

An important thing to remember, he said, is that Prudhoe engineers already have achieved "a world-class production level" from the field, recovering 11.5 billion barrels, or about 50 percent of all the oil originally trapped in Prudhoe's porous rocks.

Once gas production begins, field engineers will have a potential ace in the hole -- carbon dioxide, which will be separated from the natural gas coming out of the ground. Engineers believe they can shoot this waste gas underground to force out oil, Pospisil said.

While some tradeoff in oil production is almost certain, Foerster agrees Prudhoe likely will be ready for a gas pipeline, so long as oil is produced steadily before gas line startup.

THE POINT THOMSON PUZZLE

When it comes to Point Thomson, Foerster is worried.

State officials and industry players agree the gas in Point Thomson -- about a quarter of the North Slope total -- is vital to make a pipeline project costing $20 billion or more pencil out.

But the Point Thomson field is different from Prudhoe, and not as well understood. Much technical analysis is needed to determine the effect of producing its gas, Foerster said.

Most people regard Point Thomson as a gas field, but what concerns the oil and gas commissioners is the fate of its sizable reserves of liquid hydrocarbons -- estimated at several hundred million barrels.

"We're talking about an Alpine field or two," said Foerster, referring to Alaska's third-largest oil field.

The question has been complicated by legal wrangling in which the state is trying to revoke leases Exxon Mobil Corp. and other companies hold for failure to develop Point Thomson since its discovery 30 years ago.

Daily News reporter Wesley Loy can be reached at wloy@adn.com or 257-4590.

Posted by Arthur Caldicott on 10 Jun 2007