Kinder Morgan Marked by Spills

Jeremy J. Nuttall

TheTyee.ca

August 23, 2005

Trouble in Tuscon

Terasen suitor's many pipelines figure in several

U.S. disasters, including a very deadly one.

Kinder Morgan, the company that hopes to take over the B.C. gas utility Terasen, is “the poster child for pipeline problems,” according to Carl Weimer, executive director of the Bellingham, Washington--based Pipeline Safety Trust.

Weimer says Kinder Morgan has a poor safety record, which he attributes to the company taking over a huge network of pipelines in a short time frame. “They’ve expanded rapidly and a lot of the pipelines they took over are older pipelines. And that has undercut some of the safety,” he says.

Weimer, whose trust is funded by a court-ordered endowment created after an Olympic Pipe Line Co. pipeline in Bellingham burst and then exploded in 1999, killing three and destroying Whatcom Creek, says ongoing internal inspection is the best way to stay on top of pipeline maintenance. Weimer adds that Terasen has a good record on this front. “Hopefully the personnel won’t go through a dramatic change” during the takeover, he says, given Terasen staff’s credible record.

According to Terasen, many of their pipelines are approaching 50 years of age, and some, particularly under Vancouver, are as old as 70 years. Many of the lines Kinder Morgan took over in the U.S. are around 50 years old, says Weimer, which has resulted in several failures on its network.

Explosion killed five

The most dramatic and deadly incident had another cause, however. Five people were killed last November in Walnut Creek, California, after an excavator ruptured a high-pressure petroleum line. Gasoline filled the pipe trench and was ignited by a welding torch.

Kinder Morgan spokesman Rick Rainey told The Tyee that the incident had nothing to do with the company’s practices. “It was a backhoe operator that ruptured our pipeline, so that had nothing to do with integrity,” he says.

However, the California Department of Industrial Relations didn’t see it exactly that way. In its 20-page report on the Walnut Creek explosion, the department said the main contributing factor was that the pipeline was not properly marked: “The primary cause of the incident was that the location of the petroleum line was not known to employees working in the area.”

Negligence cited

In the end, Kinder Morgan was cited for two counts of “serious willful” and fined a total of $140,000. In the report, “willful” is defined as a situation “where evidence shows that the employer committed an intentional and knowing violation -- as distinguished from inadvertent or accidental or ordinarily negligent -- and the employer is conscious of the fact that what they are doing constitutes a violation, or is aware that a hazardous condition exists and no reasonable effort was made to eliminate the hazard.”

Right underneath that violation “serious” is defined as “cited where there is substantial probability that death or serious physical harm could result from a condition which exists -- or from practices, operations or processes at the workplace.”

The fines to the three other companies involved amounted to $51,750, less than half of what Kinder Morgan was fined for its part in the accident, even though Kinder Morgan insists the accident was not really its fault.

Another blemish on Kinder Morgan’s environmental record is a 2004 70,000-gallon diesel spill into a Northern California marsh from an old, corroded pipeline. However, according to Rainey, the company had wanted to replace the very pipeline that leaked into the marsh, and would have done so, except that California’s “cumbersome permitting process” held up the company’s attempts to change the line.

“It took us three years to even get permits. Had it been done a little more timely,” says Rainey, “we wouldn’t have had the issue of the rupture.”

Still, Kinder Morgan pled guilty in the case and paid about $3 million in penalties and restitution. The company didn’t notify the California government about the spill until 18 hours after it had occurred, a failure for which it was cited. Kinder Morgan attributed the delay to the time it took them to identify the leak and be certain there was a one.

Houses sprayed with gas

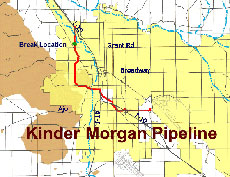

Not all of the leaks have been hard to locate. In 2003 in Tuscon, Arizona, 19,000 gallons of gasoline spilled out of another Kinder Morgan pipeline, spraying a housing development and flooding nearby streets. The resulting pipeline closure caused major gas shortages in the state.

In December 2004, a Kinder Morgan pipeline burst in the Mojave Desert in California. For 12 hours, it spewed diesel more than 70 feet into the air. The fuel seeped an estimated 50 feet below the surface and the clean up involved removing 7,500 tons of dirt from the site.

Rainey defends Kinder Morgan’s history and says that overall, “despite a couple of recent high-profile incidents,” the company has a clean record. “We have a very aggressive integrity management program, and that will be applied,” he says of the standards the company will promote in B.C.

Safety commitment lauded

According to Rainey, since the company was formed in 1997 it has increased its pipelines by 6.5 times yet spends 10.5 times more on safety and maintenence. He says the incidents have little to do with negligence. “It’s certainly not for lack of dedicating financial resources to make sure [pipelines] are safe,” he says.

Rainey says Kinder Morgan’s record is considered better than the industry average -- according to his company’s records. That sentiment is echoed by Terasen’s director of public affairs, Cam Avery. “In most quarters they’ve got above-industry-standard record,” says Avery, adding that B.C. standards would apply if Kinder Morgan succeeds in its takeover bid. “Terasen gas is regulated in British Columbia according to British Columbia standards.”

Rainey also stresses the company is actively trying to improve its practices. “Commitment to safety is our top priority,” he says.

However, Kinder Morgan has been cited for not complying with government safety standards, and for not performing emergency training. In December 2004, Kinder Morgan was fined $26,630 and promised to buy emergency equipment for a California town after failing to conduct the minimum 10 emergency drills at a Nevada oil-holding facility and for neglecting to conduct two oil-spill response drills. The safety drills were required by the Environmental Protection Agency.

Out of Enron

Kinder Morgan was formed by Richard Kinder and Bill Morgan, both former executives of the infamous energy giant Enron Corporation. Richard Kinder was the president of Enron until 1997, when he handed the reins over to Kenneth Lay, who now faces fraud charges related to the collapse of the company.

As with Lay, Kinder and his family are strong supporters of George W. Bush. Kinder’s wife raised more than $200,000 for Bush during the 2004 election, and had pledged $100,000 to the Bush campaign in 2001. According to Mother Jones, during that 2001 campaign Kinder and his wife served as regional co-chairs for Bush’s Presidential Exploratory Committee, and Kinder has given $379,745 US to the Republican party.

Terasen stockholders will vote on the sale of Terasen to Kinder Morgan in late October. If the deal is approved, Terasen could be under Kinder Morgan control by December.

Scott Webb, a Terasen gas utility spokesperson, says there is some nervousness within Terasen about the deal. There’s “a little bit of uncertainty,” he says. “This all happened very fast.” Webb added that some Terasen employees are excited that Terasen may be acquired by a company that really wants to own it.

The B.C. Ministry of Energy and Mines and the Ministry of the Environment were approached for comment on safety and regulatory issues in B.C. but were not available by press time.

Jeremy Nuttall is a Penticton radio reporter and freelance writer.

Posted by Arthur Caldicott on 23 Aug 2005