Whatcom Falls pipeline disaster - 5 years later

A BELLINGHAM HERALD SPECIAL REPORT:

Deadly fire turned families into activists, and put national focus on pipeline safety

Ericka Pizzillo and John Stark

The Bellingham Herald

June 10, 2004

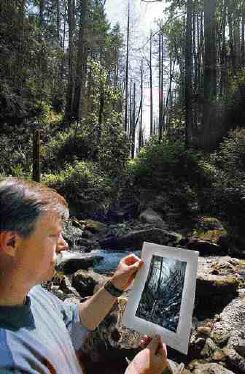

THEN AND NOW: Carl Weimer looks at a photograph of destruction in Whatcom Falls Park shot the day after the pipeline fire on June 10, 1999. He is standing in the same location where Hannah Creek enters Whatcom Creek. Weimer is the new executive director of the Pipeline Safety Trust, which was created with a $4 million endowment from criminal fines paid by Shell Oil Company. MAME BURNS HERALD PHOTO

The gasoline pipeline explosion in Whatcom Falls Park five years ago changed the way pipelines are regulated across the country, turned three families into safety advocates and created better emergency plans for city police and fire crews.

On June 10, 1999, a pipeline running underneath the park ruptured, spilling 277,000 gallons of gasoline into Whatcom Creek. The gas exploded into a fireball, incinerating 1 1/2 miles of the creek bed. Three youths who were in the park died.

"It was ugly," Bellingham Fire Chief Bill Boyd, then a captain, said at the time. "I've never seen anything like it. It was like Mount St. Helens," the Washington volcano that erupted in 1980.

Since the disaster, Olympic Pipe Line Co. has spent more than $15 million in environmental work to restore Whatcom Creek, and another $30 million on inspections and repairs aimed at heading off future problems, spokesman Mike Abendhoff said.

In March 2003, Olympic filed for bankruptcy, citing "damages sought from Olympic (and others) on criminal and civil claims totaled over $700 million," according to the court document.

The company has paid $79.3 million to settle 11 personal injury and property loss lawsuits, the court record shows.

The court could approve that bankruptcy settlement as soon as October, according to Department of Ecology spokeswoman Sheryl Hutchison.

Ecology Department officials met Tuesday with Olympic representatives to discuss when pipeline improvements and safety measures might be complete. The company has completed about one-third of the structures agreed to in earlier discussions.

City officials plan to meet with Olympic officials next week to discuss the bankruptcy proposal.

The industry

The interstate pipeline industry now faces tougher regulations and stiffer penalties because of the Bellingham disaster.

Since 1999, Congress has amended pipeline safety law, requiring more inspections, a reduction in the size of spills that must be reported to the federal government and whistleblower protections for employees who disclose problems within pipeline companies, among other changes.

BP Amoco took over operation of Olympic Pipe Line Co. in 2000 after becoming a majority shareholder in Equilon Enterprises, which was the majority shareholder in Olympic. Since then, Abendhoff said, 228 repairs have been made on the pipeline from Cherry Point to Portland.

"I really believe that all the work and time we're spending on this pipeline make it one of the safer pipelines in the country," Abendhoff said, adding that the company's safety program goes beyond what state and federal law requires.

As recently as May 23, however, a leak in an Olympic branch line in Renton spilled thousands of gallons of gasoline and touched off a fire in which nobody was hurt. Abendhoff said that incident demonstrated that no system is perfect.

"Unfortunately, it's the nature of the business," he said. "We can never say never ... but we're doing everything we can."

The nation's 2 million miles of pipelines are operated much differently than five years ago - before both the Bellingham disaster and a Carlsbad, N.M., accident in 2001, in which 12 people were killed when a natural gas pipeline exploded in a campground.

Industry representatives still talk about those accidents today, said Stacey Gerard, associate administrator for the federal Office of Pipeline Safety.

"The pipeline industry overall is more willing to come to the table," Gerard said. "It's easier for us to work with the industry today as a result of the public interest in pipelines."

National Transportation Safety Board officials were highly critical of the Office of Pipeline Safety before and after the Bellingham rupture. NTSB officials called the agency the least responsive of all agencies to which it issues recommendations.

Gerard said the Office of Pipeline Safety has made significant progress, responding not only to the NTSB's recommendations, but also to requirements from Congress. The Office of Pipeline Safety also has increased the use of orders against pipeline companies to compel action, including repairs, shutdowns or changes in their safety plans.

In the last two years, the agency has issued 30 orders against pipeline companies, compared to just five orders from 1995 to 1999.

In addition, the numbers and amounts of pipeline fines collected by the agency have steadily increased during the past five years - from zero dollars in 1999 to $831,400 last year. But many initial fines are lowered by the agency through negotiations and appeals by companies.

Federal Inspector General and General Accounting Office reports evaluating the agency's rulemaking and fine collections are due for release this summer.

The families

The families of the three youths who died in 1999 continue to lobby for tougher laws and penalties.

The families of Liam Wood and Stephen Tsiorvas now operate the Pipeline Safety Trust, created last year after a federal judge ordered that $4 million of the $15 million in criminal fines paid by Shell Oil Co. in connection with the disaster would go to the trust.

Frank and Mary King, meanwhile, have testified before Congress and at industry conferences, consistently lobbying for heavy fines, and have pledged money to build a student recreation center at Western Washington University and ballfields at Squalicum Parkway to honor their son, Wade, who died in the disaster.

Despite improvements in pipeline safety since 1999, there are still gaps in the law restricting the public's right to know about pipeline operations and safety plans, said outgoing trust director Greg Winter.

For example, a new law requires pipeline companies to identify "high-consequence areas" where large numbers of people could be in danger or creeks, lakes and drinking water sources could be threatened if a fuel spill occurred. Although the details are available to local emergency officials, the public can only find information by asking about specific locations, Gerard said.

In Whatcom County, the high-consequence areas for Olympic pipeline include the section of Bellingham and Ferndale where the pipeline runs, as well as where it crosses the Nooksack River, just south of Ferndale.

Members of the trust also want to put together report cards on pipeline companies so the public can have easy access to information about companies that might be operating in their back yard or neighborhood park.

The employees

Two former Olympic officials were sentenced to prison for their part in the disaster.

Frank Hopf, former vice president and manager of Olympic Pipe Line Co., was released from prison last February.

Hopf served six months in the minimum-security Bastrop Federal Correctional Institution in central Texas, northeast of San Antonio, according to the U.S. Bureau of Prisons. He received that sentence last year after pleading guilty to a felony violation of pipeline employee training laws in connection with the 1999 disaster in Whatcom Falls Park.

A second former employee of Olympic, Ron Brentson, has yet to serve his 30-day sentence.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Lawrence Lincoln said Brentson was seriously injured in a traffic accident after he was sentenced along with Hopf, after a guilty plea to the same charge. He will still be expected to serve the sentence after he recovers and completes physical therapy, and the court gets periodic updates on his progress, Lincoln said.

Kevin Dyvig, the employee at the controls of the pipeline when the blast occurred, pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor charge and was given a year's probation.

The city

Getting information to the public is now recognized as a critical task when disaster strikes, Bellingham Fire Chief Bill Boyd said. On June 10, 1999, the pipeline explosion took out a cell tower, land-based phone systems were overloaded and police and firefighters didn't have enough two-way radio frequencies to manage the crisis.

The city now has a dedicated radio channel to get emergency information to KGMI-AM, a Bellingham radio station, and the city's Web site and public access cable Channel 10 are also available in an emergency.

On Sept. 11, 2001, when the televised collapse of the stricken World Trade Center towers touched off a nationwide sense of danger, Bellingham's improved communications system was ready to provide reassurance to the public.

"We learned the lessons of 9-11 early," Boyd said.

The pipeline disaster also heightened awareness of the need for disaster planning among both the citizenry and public officials, said Neil Clement, Whatcom County's deputy director of emergency management.

Today, Clement said, local officials are more willing to provide funding for emergency response needs, and citizens pay more attention when they are given advice about what to do in an emergency. More people have signed up for classes in emergency response to prepare themselves to serve as volunteers in the next crisis, Clement added.

Carroll said being prepared means more than buying hardware and installing communications systems. Emergency personnel need to be trained and regularly drilled.

"There is no fail-safe system," he said. "We need to practice, practice, practice, and prepare, and be ready."

Reach Ericka Pizzillo at ericka.pizzillo@bellinghamherald.com or call 715-2266. Reach John Stark at 715-2274 or john.stark@bellinghamherald.com.

HOW IT HAPPENED

The Olympic Pipe Line Co. pipeline disaster on June 10, 1999 was created by a series of problems that began years earlier, according to the final report by the National Transportation Safety Board.

Here are its findings:

• In 1994, a contractor installing a new water line for the city of Bellingham in Whatcom Falls Park likely damaged the gasoline pipeline, which was located below the water line.

• In the five years after the water line project, Olympic failed to identify or repair any of the damage and failed to properly interpret results of internal tests on the gas pipeline.

• Olympic also failed to correct repeated, unintended valve closures in the line that originated at the pipeline's Bayview terminal in Skagit County. On June 10, 1999, a computerized monitoring system shut down a pump in Skagit County after a pressure surge burst the line in Bellingham. Olympic operators at a remote station in Renton restarted the system, allowing additional fuel to spill out of the pipeline.

• Download the complete NTSB report (PDF format, 1.1MB.)

• View photos of the pipeline disaster in the pipeline photo gallery.

MEMORIAL CEREMONY CHANGED

A public remembrance of Bellingham's 1999 pipeline disaster has been changed to 2 p.m. today on the steps of Bellingham City Hall, 210 Lottie St.

Organizers have added U.S. Sen. Patty Murray, D-Wash., to the slate of speakers.

Posted by Arthur Caldicott on 10 Jun 2004